Local Explorers Discover Shipwreck Lost in 1886 collision off Holland, Michigan

Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (MSRA) has discovered the remains of the remarkably intact steamship Milwaukee, lost after it was rammed in 1886 midway across Lake Michigan off Holland in deep water. In an unprecedented event, they announced their discovery to a live audience of 300+ people at the Knickerbocker Theater in Holland, Michigan on March 23, 2024, at their annual film festival.

“This marks the 19th shipwreck our team has found off the shores of West Michigan”, said Valerie van Heest,” who with her husband Jack van Heest coordinated the search effort.” As a non-profit agency, MSRA shares its historic discoveries with the public through books, articles, lectures, and museum exhibits.

MSRA discovered the Milwaukee in June 2023 using side-scan sonar. MSRA board of directors, the van Heests, Craig Rich, and Neel Zoss spent the balance of the summer working to film the wreck and confirm its identity. They documented the wreck using a remote-operated vehicle (ROV) assembled specifically for this project by the team’s engineer, Jack van Heest.

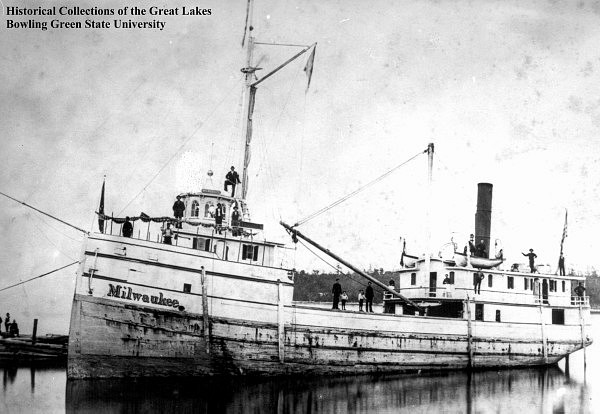

Before its loss, the Milwaukee had a varied career that spanned 18 years. The Northern Transportation Company of Ohio, among the earliest steamship operators on the Great Lakes, commissioned the ship in 1868 to join its growing fleet of passenger steamers to carry passengers and goods westward from the terminus of the Northern Railroad line at Ogdensburg, New York, to Chicago with many stops in between.

At 135 feet long with three decks (two for freight and one for passengers) the Milwaukee was sized to fit the dimensions of Welland Canal locks between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. For more than a decade the Milwaukee ran on four of the five Great Lakes carrying settlers and settlement supplies westward.

The Wall Street panic of September 1873 resulted in a deep depression. Northern Transportation Company managed to keep operating its 32 steamers through reorganization, but by 1880 the expansion of the railroads westward and the enlarging of the locks at the Welland Canal would make their fleet of 135-foot steamers inefficient.

But at only 14 years old, the Milwaukee still had plenty of life. A trend with shipping at the time was to repurpose the small passenger steamers as steam barges by removing some of the upper-level sleeping cabins to expose a long wide deck in the middle of the ship that could accommodate a much wider variety of cargo, including lumber, iron, fruit, or packaged goods. W.W. Ellsworth, an agent for NTC, purchased the Milwaukee and oversaw its conversion in 1881 at Port Huron, Michigan. He sold the ship, and it began its new career on Lake Michigan carrying all manner of cargo across the lake.

In 1883, lumberman Lyman Gates Mason of Muskegon purchased the Milwaukee for exclusive use hauling his company’s lumber to Chicago. When he enrolled the vessel under his name, documents listed it as having one deck, suggesting that it had again been converted, but there were no photographs or newspaper accounts to provide any detail. “But it was newspaper accounts of the sinking that provided the clues we needed to locate the shipwreck,” said Valerie van Heest, who developed the search grid.

Those accounts described how in the late afternoon of July 9, 1868, the Milwaukee left after unloading a cargo of lumber and set a course back to Muskegon for another load. A nearly identical ship, the C. Hickox, operating for a different Muskegon lumber company left Muskegon that evening for Chicago with a full load of lumber on its deck and towing a schooner barge also fully loaded.

The lake was calm, but there was some smoke blowing across the water from forest fires in Wisconsin that week. Both ships sailed such an exact course that at about midnight, when each was off Holland, they were bearing straight for each other.

Dennis Harrington, the watchman on the Milwaukee, first spotted the lights from the other vessel. He notified Captain Armstrong immediately. Captain O’Day of the Hickox saw the same thing. Navigational rules were specific: both ships had to slow down, each had to steer to starboard (right) to avoid a collision, and each had to blast their steam whistle to signal their course change.

But the old superstition that bad things happen in threes would haunt the captains of both ships that night. Neither Captain slowed down because visibility was generally fine, but suddenly a thick fog rolled in rendering them both blind. Captain O’Day quickly made a turn, but when he tried to blast his steam whistle, the pull chain broke.

Unable to see or hear what the other ship was doing, Captain Armstrong froze. When the fog briefly parted, the Hickox was upon the Milwaukee. Armstrong made a fast turn, but the ships were traveling too quickly. The Hickox plowed into the side of the Milwaukee, popping hull planks, nearly capsizing the ship, and sending lookout Harrington tumbling into the water. Both Harrington and the Hickox disappeared into the smoke and fog.

Pandemonium broke out on the Milwaukee. The captain went below deck and saw water pouring in. He blew a distress signal to gain the attention of the ship that had rammed him, and ordered the pumps turned on. He and the crew rigged a “canvas jacket” by stretching the sail over the damaged side of the ship to reduce the onrush of water. Several people escaped in the lifeboat and met the Hickox as it struggled to find the Milwaukee. Another steamer, the City of New York, arrived, having answered the distress call, and together with the Hickox sandwiched the Milwaukee between them and rigged ropes to try to keep the damaged ship afloat.

Their efforts failed. Almost two hours after the collision, the Milwaukee’s stern dipped beneath the surface, and the ship plunged to the bottom. By then, everyone had made it to safety aboard the Hickox.

“News accounts of the accident, as well as the study of water currents, led us to the Milwaukee after only two days searching,” says Neel Zoss, who spotted the telltale image on the side scan sonar.

Weeks later, the team laid eyes on the Milwaukee, which had been resting patiently on the bottom for 137 years as if just waiting to be found.

“Visibility was excellent” says Jack van Heest, who piloted the ROV. “We saw the forward mast still standing as the ROV headed down to the bottom.” The ship rests upright on the bottom facing northeast just as it was heading that night.

But as the explorers watched the video in real time they saw something unexpected. “The pilothouse on the wreck looks nothing like the octagonal pilothouse in the historic photo,” noted Valerie.

“In studying the video,” said Craig Rich, “we realized that Lyman Gates Mason, who owned the Milwaukee, had made both the pilothouse and the aft cabin smaller in order to maximize the amount of lumber the ship could carry on each run.”

The team noted how important this discovery is because it provides information about the ship for which no other records exist.

As it turned out, following an inquest, both Captain Armstrong and Captain O’Day lost their licenses for a time after this accident because neither captain slowed down as they were supposed to.

Slowing down in the face of danger may be the most important lesson this shipwreck can teach.

Photos used with permission, Historical Collection of the Great Lakes, Bowling Green State University.