The most horrific loss of life in a Muskegon-area shipping accident was the tragic sinking of the Muskegon in 1919. As many as twenty-nine people may have perished during one of the deadliest days in Muskegon history.

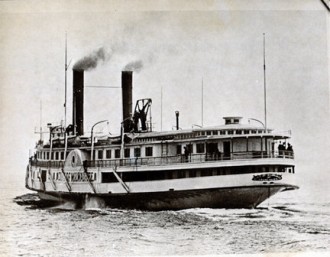

The iron-plated, side-wheel passenger and package freight steamer began life as the City of Milwaukee on February 11, 1881, at the Detroit Dry Dock in Wyandotte, Michigan, under the design and construction prowess of the famed maritime engineer Frank Kirby for the venerable Goodrich Line. At 231 feet long and 34 feet wide, the City of Milwaukee was the pride of the line. With twin boilers and a massive walking beam engine built by the W. A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, the vessel generated an impressive (for the time) 1,500 horsepower.

With such a long career, the vessel served a number of owners including Goodrich from 1881 to 1883; the Detroit, Grand Haven & Milwaukee Railway Company from 1883 to 1897 the Graham & Morton Transportation Company from 1897 to 1917; and the Crosby Transportation Company from 1917 until the loss in 1919. Named Holland in 1904 while under the G&M flag, the vessel received the name Muskegon from the Crosby Line owners just two months before its final accident.

The vessel suffered a number of incidents and rebuilds over the decades including an 1885 accident when the walking beam engine shattered and pushed a connecting rod through the tipper deck. Over the winter season of 1900/1901, Graham and Morton added an entirely new upper deck of cabins and a new theatre to offer entertainment to passengers. In 1903, the company added sixty more staterooms.

Shortly after 4 a.m. on October 28, 1919, while coming into Muskegon on a regular run from Milwaukee, the Muskegon went out of control in a westerly gale and rammed the south pier head.

Shortly after 4 a.m. on October 28, 1919, while coming into Muskegon on a regular run from Milwaukee, the Muskegon went out of control in a westerly gale and rammed the south pier head.

The vessel quickly sank, trapping many of the passengers below decks as it broke apart. Although the newspapers gave conflicting information on the number of victims, perhaps thirty people perished in the sinking, both passengers and crew.

Many more may have drowned if not for the efforts of Coast Guardsman Ransom A. Jakubovsky, who was on watch at the U. S. Coast Guard station at the time. “I saw the boat coming towards the piers,” he told reporters. “There was a gale but the ship seemed to be making good headway. It came alongside the piers and was caught by the undertow and struck. I sounded the whistles and the Life Savers were out within two minutes. By that time, however, the boat was being pounded to kindling. I had my flashlight in my pocket and by using that, many of the passengers were able to get off,” continued Jakubovsky. “It was so dark we couldn’t see and my flashlight was the only aid these people had. I threw my light so people could jump, but I could not throw it everywhere.”

The Muskegon‘s captain, Edward Miller, was despondent after the sinking. The Muskegon Chronicle quoted him saying, “They probably will want to send me to hell. I stayed on the deck until it was going to pieces. In fact, it was being washed away under me. Then I jumped to the pier.”

When daylight came, large masses of wood and debris choked the channel. Passengers’ clothing, trunks, cases of food, tobacco, and other debris floated in the channel and washed up on the beaches. Hundreds of people on the piers fished with sticks and pike poles to retrieve some of the more valuable items. Flotsam littered the beach as well. Coast Guardsmen dealt severely with the looters while gathering personal effects together and sending them to the morgue.

As the inquiry into the accident got under way, officials brought in hardhat diver Robert Love to search for bodies and hired others to drag the harbor entrance with grappling hooks. Love reported the hull was crushed up against the pier and said he could not locate any additional bodies. The list of victims in local newspapers grew and changed over the ensuing weeks and finally totaled twenty-nine people, both crew and passengers.

As the inquiry into the accident got under way, officials brought in hardhat diver Robert Love to search for bodies and hired others to drag the harbor entrance with grappling hooks. Love reported the hull was crushed up against the pier and said he could not locate any additional bodies. The list of victims in local newspapers grew and changed over the ensuing weeks and finally totaled twenty-nine people, both crew and passengers.

Twelve years later, in July 1931, the Muskegon chronicle reported that employees of the Sullivan Dredging Company, contracted to remove the old south pier, had rediscovered evidence of the wreck. The story read, “Divers employed to see that the floor of the lake is cleared of all remnants of the old pier to a depth of 27 feet have been finding tools, angle iron, silverware and other relics of the Muskegon, which went down with a loss of about 30 lives in October 1919.”

Info from “Through Surf and Storm: Shipwrecks of Muskegon County, Michigan” by Craig R. Rich