It is an exciting moment in the life of anyone who loves history when we get a window to the past is opened. Mother Nature opened that window the first week of December 2018 when her lake gale calved off a giant section of a dune on the south side of the White Lake channel just west of the White River Light Station Museum. Where there used to be a slope to the beach, suddenly there was a precarious bluff. And below the bluff, once buried under some five to ten feet of sand, lay exposed a time capsule from the past. Even casual observers knew what they were seeing: the backbone and ribs of a ship, or rather the keelson and frames in maritime jargon. Some of them grabbed their cell phones, snapped pictures, and posted them on Facebook

Craig Rich, co-director of the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association re-posted those photos, and the story went viral. Some 30,000 pairs of eyes saw the shipwreck. Over the next week, many hundreds of people flocked to see the old wreck. And they did so without even the hope of finding a gold coin, because everyone who lives near Lake Michigan knows that lake boats only carried such cargos as lumber, grain, coal, or stone, among other ordinarily raw materials.

This was not the first time that particular shipwreck had been seen. In 1974 Pete Caesar, the first curator of the museum in the recently decommissioned White River Light Station spotted the same wreck. Apparently, Mother Nature had been hard at work back then too. He dug through the archives and found photos taken in 1942 when it had been visible. He recognized it immediately as the remains of a schooner and began trying to identify it. He eventually dubbed it L.C. Woodruff, a 170-foot long schooner sunk in 1878. Historic news accounts told a dramatic story of storm, disaster, rescue-gone-bad, death, and resurrection when some of the crew struggled out of the surf safe and sound. Back in the day, and particularly before the lighthouse was erected in 1875 at White Lake, more than a dozen schooners met their fate close to shore when storms made it difficult for those ships to maneuver. Shore is no friend to a sailor in bad weather.

With a new museum to run, Pete Caesar put out an appeal for support and funding to recover and display the wreck before Mother Nature could reclaim it. However, he was met with rejection. No one had the money or space to conserve and display such a large artifact. At that time, the Mystery Ship Seaport in Menominee, Michigan was already feeling the pain in their wallets and seeing the degradation of the schooner Alvin Clark, an intact ship raised just a few years earlier from deep water in Green Bay. Soon thereafter the museum put on display the stem of the vessel (the forward most timbers) but whether it came from this wreck or another is currently being looked into. It still stands there today, though considerably decayed. Only oral history passed down to the current lighthouse museum curator, Matt Varnum, tells us it was recovered in the 1970s. In 1980 Caesar published his first of many books: L. C. Woodruff: Lake Michigan’s Ghost Ship Returns.

Now in 2018, with the news going viral, people began saying that the Ghost Ship Woodruff had returned once again.

However, we recalled that back in 2005 a beachcomber had come across the remains of a shipwreck in shallow water about a mile north of the White Lake Channel. The timbers were long and large. Wisconsin historian Brendon Baillod reviewed photographs of the wreck and suggested it was more likely the Woodruff than the wreck at the channel.

Craig Rich, who had written about the Woodruff in his book Through Surf and Storm, looked into this further and noted that while all the historical accounts suggest that while the Woodruff spent some time anchored off the White River Channel during the storm back in November 1878, waves swept it north and it eventually grounded north of the channel.

Over the past twenty years since we founded the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, our team has surveyed and identified more than two dozen shipwrecks along the West Michigan shore, not to mention another two dozen in deep water. It was time to dig out our shovels, tape measures, and slate boards and head up to the White River Light Station Museum to attempt to officially confirm or refute Caesar’s identification of the wreck.

MSRA co-director Valerie vanHeest invited Eric Harmsen, an archaeologist who now manages the Port of Ludington Maritime Museum, to join her to document the remains. They arrived armed with

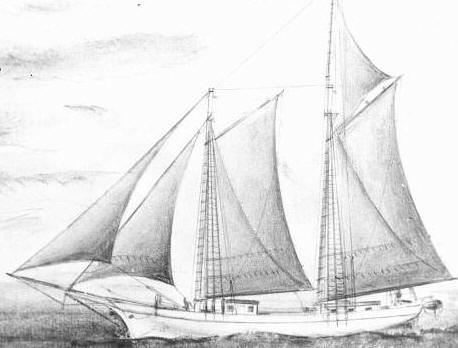

Therefore only three candidates remained: The small, 67-foot long Madison, the medium 124-foot long Contest, or the large 170-foot Woodruff, if Caesar knew something we didn’t. There are no historic photos of any of these ships.

Varnum, who works for the Sable Point Lighthouse Keepers Association, led us 500 feet west from the lighthouse to the wreckage. At the beach, the MSRA team carefully negotiated our way down the dune that shifted under our every step. Mother Nature had been at work again, churning up the surf to give us a vision of what it must have been like the day the mystery schooner battled the elements and lost.

Then we came face to face with the past. The bow, obvious because the frames were shorter at one end, faced south, and we approached from the stern stepping gingerly over the structure. Waves crashed over the starboard frames. Walking along the port side, we came to the bow. The stem was no longer in place, but whether it broke off, just degraded naturally, or was recovered and put on display cannot be known. We got right down to the business of measuring the length, as that would provide the best opportunity to identify the wreck. From the bow to the last portion of the structure visible before the dune enveloped it, the keelson measured 66 feet plus about six feet to account for the missing stem. We used the shovel to burrow some distance into the dune and could clearly see that the keelson continued with no end in sight, so we ruled out the 67-foot Madison.

We inspected an interesting feature along the keelson. A slab of wood angled down through a slot in the keelson. It appeared to be the centerboard, still in position. While sailing, it helped stabilize the ship. Now, it seemed to lock the remains into the sand. From years of examining wrecks and

There is little historical data about the Contest and no dramatic accounts of its final accident. From official enrollment documents, we learned that the 126-foot long, two-masted schooner was built at Buffalo, New York in 1855 for Hart Newman & Co. It sailed on Lakes Erie, Huron, and Michigan, operating, according to records, in the grain trade.

The Contest had many owners. Here’s the history:

Pratt, S., (1855); Mixer, H. M., (1856); Taylor, A. C., (1858-1864); Jewett, (1860-1864); Winslow, Henry C., (1865-1866); Gunderson, M., (1866); Winslow, N. C., (1866); Morgan, S., (1869); Goodrich, J., (1870): Coble, J., (1871); Cobb, S., (1874-1880); McNulty, M. J., (1882).

It had many masters:

Pratt, (1855); Newmann, E., (1856); Rogers, J., (1858); Collins, Thomas, (1865); Gunderson, (1866); Hays, J., (1869); Coble, J., (1871); Day, S., (1874); Elliott, G. B., (1880); Bessell, William, (1882).

And, it suffered many incidents:

- October 1855, South Passage, Lake Huron, collision, (Bark, American Republic), repaired, $2,000 loss.

- October 1858, put in at Detroit, having lost anchors, chains and sails,

refitted, $1,100 loss. - October 1858, damaged cargo of wheat, $200 loss.

- November 1859, Buffalo Harbor, collision, (Propeller, Susquehanna), repaired,$400 loss.

- April 1868, Lake Huron, sprang a leak, cargo lost, repaired, $11,400 loss.

- September 25, 1868, Point Au Pelee Island, Lake Erie, ashore, sank and

raised, $11,000 loss.

Even the vessel’s official enrollment papers told a story. From 1870-1874, it was enrolled as a barge, which meant that other ships towed it from place to place, but it was

Even now, Mother Nature already has done her handy work and covered the wreck back up. Even while we were there, sections of the bluff hanging over the wreck had begun falling onto the timbers. But for another brief period of time, we have had a glimpse into the past, to the days when sailing ships dotted Lake Michigan and when sailors risked their lives on every delivery run.

Thank you to Valerie vanHeest and Craig Rich for collaborating on the research, Eric Harmsen for his expertise, Kevin Ailes for the aerial photographs, and Brendon Baillod for his input.