June 23, 1950. It was the day before North Korea invaded South Korea

prompting President Harry S. Truman to commit US forces to defend the country.

On the radio, Nat King Cole, Doris Day and the Ames Brothers were singing the latest tunes — just a few years before rock and roll would debut.

In the few homes equipped with that new invention, the television set, families were watching Snooky Lanson singing the week’s top songs on “Your Hit Parade”.

In New York, the evening of Friday, June 23, 1950, was a warm, but pleasant night. Passengers who boarded Northwest Airlines Flight 2501 bound for Seattle, Washington, with a scheduled stopover in Minneapolis, Minnesota were looking forward to a long, but comfortable flight.

Flight 2501 was a Douglas DC-4 airliner with four Pratt & Whitney, R-2000 “Wasp” engines. These reciprocating piston, propeller engines could power the converted World War II C54 transport to a maximum airspeed of 280 miles per hour. The flight lifted off on time from New York’s LaGuardia airport at 7:30 PM and headed west under clear skies.

The pilot was 35-year-old Captain Robert C. Lind of Hopkins, Minnesota. In the right-hand seat was co-pilot Verne F. Wolfe, also 35, of Minneapolis. 25-year-old stewardess Bonnie Ann Feldman was in the passenger compartment taking care of 55 passengers, identified as 27 women, 22 men, and six children.

The uneventful flight passed safely over Cleveland, Ohio, and continued west toward Minneapolis, Minnesota — a major hub for Northwest Airlines. As the DC-4 passed over Battle Creek, Michigan at 11:51 PM Eastern time, Captain Lind notified Northwest’s Air Traffic Control Center at Chicago by radio that he estimated passing over Milwaukee at 11:37 PM Central time. He was flying level at 3,500 feet.

As the plane reached the lakeshore at 12:13 AM EST that evening, Captain Lind, knowing of storms over Lake Michigan, requested clearance from air traffic control to 2,500 feet. He was denied due to other traffic in the area.

That was the last communication from Flight 2501. Her disappearance marked the largest aviation disaster in world history to that point.

The DC-4, used by Northwest Airlines for Flight 2501 was a sturdy and reliable aircraft. It had four Pratt and Whitney, R2000 “Wasp” piston engines that could generate 1,450 horsepower.

The development of the DC-4 dated back to 1938 when United Airlines conceived the first four-engine, long-range airliner. They hired Douglas to devise the highly ambitious DC-4E (“E” for experimental). This four-engine behemoth was flight tested in 1939. It was roughly three times the size of its predecessor, the DC-3, with a wingspan of 138 feet and a length of 97 feet. It could potentially fly nonstop from Chicago to San Francisco. However, the DC-4E never flew commercially.

Late in 1939, the lone DC-4E prototype was sold to Japan. This was ostensibly for use by a Japanese airline, but the buyer turned out to be a front organization for the Japanese Navy and the craft quickly disappeared. The quick disappearance of the airplane was attributed to a training crash in Tokyo Bay but, actually. It was disassembled in an aircraft factory and used as the model for a very similar four-engine bomber that, thankfully, never got beyond the prototype stage.

Boeing also could not get beyond the prototype. All the groundbreaking new technology on the DC-4E meant that it was costly, complex, and had higher than anticipated operating costs, so Douglas thoroughly revised the design, resulting in the smaller and simpler definitive DC-4 / C-54.

The U. S. Army Air Force commandeered the first batch of DC-4s right off the assembly line in 1942. The plane was given the military designation “C-54”. Production orders followed and, to meet the demand, Douglas started a second assembly line in Chicago, Illinois, which would eventually produce nearly 60 percent of all C-54s built.

C-54s were first delivered on March 20, 1942. They saw service in every theater of World War II. In time, they became the military’s primary transport aircraft to operate across both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

In the three years prior to V-J Day, C-54 crews made nearly 80,000 crossings of the North Atlantic and only three aircraft were lost. The first dedicated Presidential aircraft was the lone VC-54C, which was modified with a special hydraulic lift for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s wheelchair. Nicknamed “Sacred Cow,” the aircraft was used to take FDR to the Yalta Conference. President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947, creating an independent Air Force, while on board this aircraft on July 12, 1947. The “Sacred Cow” is now on display at the US Air Force Museum.

Winston Churchill, General Douglas MacArthur, and General Dwight David Eisenhower used C-54s as their personal aircraft. On September 2, 1945, a C-54 crew made a record run of 31 hours, and 25 minutes between Tokyo, Japan, and Washington, D. C., to deliver the first films of the Japanese surrender ceremony on board the U. S. Navy battleship USS Missouri.

“Flight Simulator 2004” NORTHWEST AIRLINES DOUGLAS DC-4, by Arik Hohmeyer, Chris Grabow & Dale DeLuca

As was the case with the earlier DC-3 or C-47, the end of the war meant that many of the aircraft were declared surplus and sold to the world’s fledgling commercial airlines. Subsequently, Douglas built 78 additional DC-4s to fill new orders.

The C-54 which would later become Flight 2501 was built for the US Air Force by Douglas in Chicago in 1943. After the war, she was converted to commercial passenger use.

On the evening of June 23, 1950, a DC-4 with certification number 10270 and tail number N-95425, owned by Northwest Airlines and designated Flight 2501, was loaded with 2,500 gallons of fuel, 80 gallons of oil, and 490 lbs of an express; and was expecting 55 passengers. The fully loaded craft weighed in at 71,342 pounds, just 58 pounds below the maximum permissible take-off weight.

Captain Lind had flown for Northwest Airlines since 1941. He was checked out on DC-4 type aircraft and qualified on the Milwaukee to New York segment five years earlier. He maintained his qualification in DC-4s, logging almost 200 hours on that aircraft, and had flown over the route continuously.

In the 90 days prior to this flight, he had flown 105 hours in DC-4 aircraft and made 15 round trips on the Minneapolis to New York and Minneapolis to Washington routes. Captain Lind also had over 900 hours logged flying solely on instruments. Just 4 months before this flight he completed a Civil Aeronautics Administration physical and he had a total rest period of 24 hours since his last flight. If anyone was prepared for this flight, it was Captain Robert Lind.

Co-Pilot Verne F. Wolfe had been with Northwest Airlines almost as long as Captain Lind had. He was a capable pilot in his own right.

The crew checked in with Northwest flight control operations center at LaGuardia Airport to prepare for the flight. The weather all along the route was carefully checked and a flight plan was arranged to avoid unfavorable conditions and bring the plane in on time.

While Lind and Wolfe were taking care of flight preparations and Bonnie Ann Feldman was preparing the cabin, baggage handlers loaded the plane with the passenger’s luggage. The flight crew then ran through their preflight checklist while the passengers boarded.

The engines were geared up one at a time and the plane made its way from the tarmac to the runway. The flight plan called for a cruising altitude of 6,000 feet to Minneapolis. Aware of a storm brewing in the Midwest, Captain Lind requested a cruising altitude of 4,000 feet. He was denied due to other assigned traffic at that level.

By the time Flight 2501 reached Cleveland, Ohio, at 10:49 PM Eastern Time, Captain Lind’s request to drop to 4,000 feet was approved by Air Route Traffic Control. 40 minutes later the pilot was instructed to drop to 3,500 feet to avoid an eastbound flight at 5,000 feet, which was experiencing severe turbulence over the Lake. They were expected to pass each other near Battle Creek, Michigan, and the standard separation of 1,000 feet would not be sufficient due to the turbulence.

By 11:51 PM Eastern Time, Flight 2501 had entered the vicinity of the growing storm. Captain Lind reported that he was over Battle Creek at 3,500 feet and would reach Milwaukee by 11:37 PM Central Time. As he neared the lake shore, he made his last transmission, requesting a further drop in altitude to 2,500 feet. He never stated a specific reason. The request was denied.

On the other side of the lake, just before midnight Central Time, Northwest Radio at Milwaukee advised New York, Minneapolis, and Chicago that Flight 2501 was overdue reporting in at Milwaukee. At that point, all Civil Aeronautics Administration radio stations attempted to contact the overdue flight on all frequencies, but to no avail. Northwest Air Traffic Control alerted air-sea rescue facilities to stand by. Flight 2501 was missing!

By dawn’s light, it became clear that the DC-4 had crashed. At 5:30 AM Saturday, June 24, the plane officially was presumed lost, as the fuel supply would have been exhausted by that time. At daybreak, the search and rescue teams began an intense search on the fog-covered lake.

The US Navy, US Coast Guard and State Police from Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Indiana were all involved in the search. 13 hours later — at 6:30 Saturday evening — the US Coast Guard cutter Woodbine found an oil slick, aircraft debris, and an airline logbook floating in Lake Michigan many miles from shore. At 5:30 AM on Sunday, June 25, sonar work by the US Naval vessel Daniel Joy near the oil slick revealed several strong sonar targets.

The Coast Guard vessels Woodbine, Mackinaw, Hollyhock, and Frederick Lee focused on the recovery of floating debris, which included a fuel tank float, seat cushions, clothing, blankets, luggage, cabin lining and, tragically, body parts. At the time, authorities wanted to determine whether the plane suffered a mid-air explosion, or whether it struck the water intact. These small pieces would be the only clues they had.

Small bits of debris floated endlessly over the surface of the fogbound lake. The airplane, along with 58 men, woman and children had disappeared, leaving few clues as to what had occurred 3,500 feet in the air. The loss of Northwest Airlines Flight 2501 represented the worst commercial aviation disaster to that time.

Initial reports suggested the plane exploded in mid-air, with debris falling into the lake between Glenn and South Haven, Michigan. Officials began discovering debris and body parts Saturday and Sunday over a four-mile area about 12 miles northwest of Benton Harbor.

Berrien County Prosecutor Louis Kerlikowski and U. S. Coast Guard officials initially speculated that the plane may have “twisted” in the high winds, causing a spark, which ignited the fuel tanks. Kerlikowski stated to the local paper, “It must have been a terrific explosion to disintegrate the bodies so badly.”

Coast Guard Captain Nathaniel Fulford said he doubted there was any piece of the wreck “big enough to be worth diving for.” He actually refused a request by Northwest Airlines to lower a diver into the 200-foot deep water. According to the Holland Sentinel, Fulford said, “I don’t consider it the Coast Guard’s duty to perform recovery duty in this case.” It was reported that Northwest then requested a Navy diver.

Captain Carl G. Bowman, skipper of the U. S. Coast Guard cutter Mackinaw told the United Press bureau at Detroit by radiotelephone that “Tiny pieces keep floating to the surface all through the area.” He said his men found hands, ears, a seat armrest and fragments of upholstery. Fulford said the largest piece of wreckage was “no bigger than your hand.”

A week later, portions of the bodies of two women were discovered — one about two miles north of South Haven and the other about seven miles north, at Glenn, Michigan.

The Coast Guard sent the cutters Mackinaw, Woodbine, Hollyhock, and Frederick Lee to the scene over the next few days to assist in the search effort. The cutters were employed to recover as many pieces of floating wreckage as possible and to ferry reporters and officials from shore to the wreck site.

Numerous sensational newspaper reports detailed the recovery of small parts of bodies, clothing, wallets and other personal effects by the Coast Guard. At one point, workers were dipping their hands into the lake to recover body parts. Authorities in South Haven closed the popular “South Beach” for nine days after the crash, due to the large number of body parts that washed in among the bathers. It was re-opened on July 3 for the holiday crowds.

A pair of boy’s pants was identified as belonging to 8-year-old Chester Schaeffer who was traveling with his mother Mrs. Oscar Schaeffer of Port Chester, New York. A wallet belonging to Frank G. Schwartz of New York City was found to contain papers indicating he was on the way to St. Paul to witness the marriage of his daughter.

On Monday, June 26, 950, the South Haven Tribune quoted retired U. S Navy man, Lt. Cmdr. R. T. Helm, as saying he had witnessed the plane fly over his home at 12:20 am. “Minutes later”, he said, “there was a terrific flash out in the lake.” He speculated the pilot was looking for a place to land. He told the United Press, “I heard the plane over my home about 12:20 AM Saturday. I took a look out of the window and he seemed to be flying pretty low. How low, I don’t know.” Helm later was ordered to testify at a hearing in Chicago.

On Tuesday the 27th, the Tribune reported the Coast Guard was conducting dragging operations in an attempt to locate a large enough piece of wreckage to warrant the lowering of hardhat divers to the lake floor. The following day the Navy’s divers spent about 30 minutes searching for wreckage in the dark water.

A week later, one of the newspapers reported, “Two divers searched the muddy bottom of the lake for six hours, but found no trace of the missing plane.” It was reported by the divers that they sank into two feet of mud on the lake bottom and that visibility was less than one foot. The area searched was about 16 miles north and west of St. Joseph in 150 feet of water.

The Tribune also quoted a Douglas Aircraft Company investigator as speculating that the plan had turned onto its back and plunged into the lake upside down. He stated there had been eight cases of this happening in high winds, but that pilots usually were able to pull out of the fall within 6,000 feet. Since Flight 2501 was flying only at 3,500 feet, the pilot did not have a chance to right the plane before impact.

By Wednesday, June 28, 1950, newspapers were relating sensational eyewitness reports from residents in the Glenn, Michigan area. William Bowie, who operated a restaurant/gas station in the tiny crossroads of Glenn vividly related to the Holland Sentinel the story of how he was sitting in front of his station at 12:15 AM on Saturday and saw the plane cruise over the area, heard its motors “plunk” twice and saw a “queer flash of light.” He claimed to have ten witnesses to the incident. Four of them spoke with reporters including Mr. and Mrs. Bowie, Danny Thompson, and Arnold Rapp. Bowie was later flown to Chicago to testify during the hearing into the incident.

All were sitting in their cars in front of the gas station waiting for the power to come back on after a fierce lightning storm had caused an outage. They saw the plane approach from the northeast; follow the highway almost to Glenn, then veer out (west) over the lake. They contend the plane’s engines were not operating properly and one of them reportedly yelled, “Bring that plane down here buddy. We’ll fix it up for you!” Thompson stated the plane’s engines sounded “like a stock car with a blown head gasket.” Bowie reported a funny yellow light trailing from the wing.

Bowie’s wife stated, “All of a sudden there was this flash. It was a funny light. It looked like the sun when it goes down. It only lasted a second and then was gone.” The witnesses say the plane was not more than 2,000 feet off the ground. Other witnesses included 30-year-old William Bowie Jr., Mrs. June Herring, Ivan Orr, Leo Dorman, and several others.

By Wednesday, July 12, local fisherman Wallace Chambers reported snagging his nets on something approximately 4 miles southwest of South Haven in 72 feet of water. A small, twisted piece of light metal was pulled up in the net and turned over to the Coast Guard. Later analysis by the Civil Aeronautics Board led to doubts the metal was from the DC-4.

Six months after the loss of Flight 2501, and after careful analysis of the floating remains and communication records, the official cause of the disaster was listed as “unknown”. No cause for the loss ever was determined. No major piece of wreckage ever was found. Today, Flight 2501 is listed on nearly every UFO website as a strange anomaly since some in the Wisconsin area reported a bright light over the lake about two hours after the event.

The loss of Flight 2501 represented the largest loss of human life in a commercial aviation accident up to that point in 1950. Since then other tragedies such as the shooting down of Korean Airlines KAL 007 in 1983, the terrorist bombing of Pan Am flight 103 in Lockerbie, Scotland, or even the loss of John Kennedy Jr.’s private plane off Martha’s Vineyard all remain in our memories. The details may be forgotten, but the horrible losses never will be.

But if you ask the average West Michigan senior citizen if they recall the loss of Flight 2501, they have either vague memories or none at all. The crash remained in the news for only about two weeks. Once the area beaches had been cleaned up and re-opened for the 4th of July holiday, the media moved on to report other news.

Because Flight 2501 originated in New York en route to Seattle, none of the 58 victims was from the local community. Had the lost passengers been local West Michigan residents like the passengers aboard the ill-fated steamer Chicora 55 years earlier, then the disaster may have had more impact on residents than just the closing of their local beaches.

Twenty-first Century Hunt for Flight 2501

Since 2004, the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association has spearheaded the research and partnered to attempt to locate the wreckage of Northwest Flight 2501 in a multi-year survey operation.

In 2004, Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (MSRA) began a joint venture project with nationally claimed author/explorer Clive Cussler, who operates the nonprofit organization National Underwater Marine Agency (NUMA), and mounts expeditions around the world to find the world’s most famous lost vessels. Cussler funded the survey services of sonar operator Ralph Wilbanks, of Diversified Wilbanks, his wheelsman Steve Howard, and additional crew members, sending them to South Haven, Michigan, to conduct sonar surveys in collaboration with MSRA within a 500 square mile area of probability developed by NUMA.

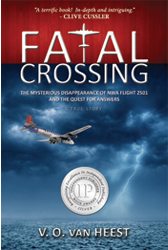

During the research phase of this project, MSRA board member Valerie van Heest, who later wrote the book Fatal Crossing, has located nearly all 58 families who lost a loved one in this accident. The search proceeded with renewed importance to offer closure to those families.

Between 2004 and 2013, while NUMA conducted side-scan sonar operations for about one month each spring working out of South Haven, Michigan, the team did not find the wreckage of the airplane, but Wilbanks did locate nine shipwrecks. MSRA researched, dived, and documented those shipwrecks, and those wrecks are profiled elsewhere on this website.

Cussler discontinued his team’s participation in 2013, but new leads developed by the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association drew him back in 2015, 2016, and 2017 to continue the hunt. Wilbanks found two new shipwrecks, again documented by MSRA, but Flight 2501 remained elusive.

Concurrent with its work with NUMA — and with NUMA’s approval — MSRA partnered with Great Lakes wreck hunter David Trotter of Undersea Research Associates to conduct expeditions in a different area of about 50 square miles south of the original search. In 2013, 2016, and 2017 MSRA and Trotter covered 80 percent of the new search area but still did not turn up the wreckage.

In 2018 MSRA began its own operation using a side scan sonar that had been donated by MSRA associate Kevin McGregor, but could only cover territory in water less than 150 feet because that unit had limited range.

In 2019 after a successful fundraising campaign, MSRA was able to acquire its own side scan sonar capable of much deeper depth and greater range. Board member Jack van Heest designed and built a cable reel capable of deploying the sonar cable.

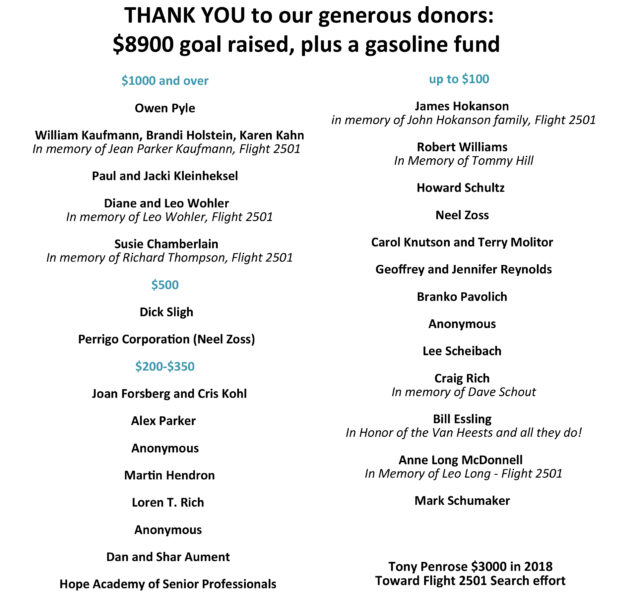

The organization is very appreciative to the individuals and companies listed here for allowing the team to continue its independent effort, as well as long-time MSRA member Richard Sligh and South Haven-based pilot Tony Penrose, who donated toward the gasoline fund.

That year the team was able to make great headway in covering more territory and the search effort was the subject of a two-hour special episode of the hit television series Expedition Unknown called “The Vanished Airliner.”

While the wreckage has not yet been found, the production provided a very good overview of the efforts required to conduct a search and the frustrations when objects other than the airliner are found.

The search effort will continue in 2020

Due to Covid-19 Shutdowns, the March 25, 2020 fundraising event had to be canceled. If you would like to support the effort, please consider making a charitable donation here.

Visit the Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, Michigan, to see the traveling exhibit about Flight 2501 called “Fatal Crossing.” It is designed by MSRA board member Valerie van Heest, and originally appeared at the Michigan Maritime Museum. It includes personal items from a passenger found floating in the waters of Lake Michigan immediately after the accident.