N 42° 22.760′, W 086° 27.427′, WSW off South Haven harbor, 160′ deep

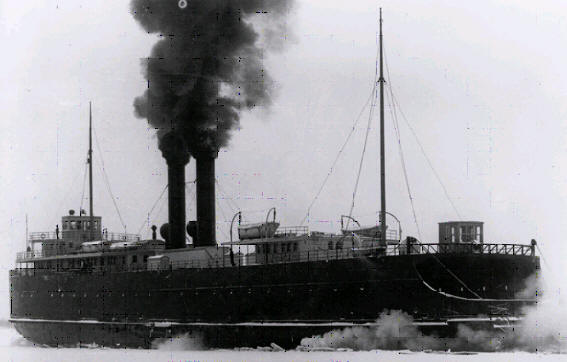

The Great Lakes car ferry Ann Arbor No. 5 was built by the Toledo Shipbuilding Company in Toledo, Ohio as hull # 118. She was 360′ long with a 56.3′ beam and an 18.9′ draft. At the time of her launch in November 1910, the Ann Arbor No.5 was the largest ferry on the lakes. It was also the first ever launched with a sea gate; a safety device designed to keep water from flooding in over the low stern. With four tracks and a capacity of 30 railroad cars the Ann Arbor no. 5 was a behemoth.

The vessel was fitted with two triple expansion engines, 21″ + 33″ + 52″ x a 40″ stroke. Steam was provided by four scotch boilers 13’6″ x 12′ capable of 185 PSI. The engines and boilers were built by Marine Boiler Works of Toledo and generated 3,000 horsepower.

For over a half-century, the Ann Arbor no. 5 worked the Great Lakes until, like all car ferries, she outlived her usefulness. She was converted to oil in 1964, then sold to Bulk Food Carriers of San Francisco in 1966. The old ferry then was swapped back and forth for a number of years in the federal government’s ship exchange program.

The Ann Arbor no. 5 was sold to Bultema Dredge & Dock Company in 1967 for $27,775. It was cut down and used as a temporary break-wall during the construction of the Palisades Nuclear Power Plant near South Haven from 1967-1969.

The AA5 broke up during severe storms over the winter of 1969-1970. According to historical documentation the hull was supposedly clam-shelled and scrapped. But if that was true, then how did a portion of the ship come to rest eight miles off shore in 160 feet of water?

After a thorough investigation, Michigan Shipwreck research Associates has connected with individuals who owned and operated Bultema Dock and Dredge and learned the truth about the fate of the Ann Arbor No. 5.

Once Bultema’s work laying intake pipes at the Palisades Plant was complete, it was clear that the barge was too damaged and broken to serve any further use. Broken in two places, Bultema cut the forward section of the once magnificent car ferry into manageable pieces, hoisted them aboard a working barge and hauled the debris to the Padnos Scrap yard in Holland, MI.

Bultema’s principals felt that the aft 150 feet of the Ann Arbor no. 5 was floatable and could be towed intact to the scrap yard, requiring less time and effort than a clamshell operation. Utilizing one of their tug boats, they were able to pull the severely damaged vessel up from her position as a break wall and float her behind the tug. With a number of pumps aboard this derelict portion of the barge, they were able to keep it afloat as they headed west, away from the power plant.

Soon after turning north on a course for Holland, a small section of the water tight wall started to leak and the marine contractors knew that they would probably lose the vessel. Fighting to keep the last main pump operational, John Bultema II, then only 20 years old and working as a diver for his father’s company, lost the battle to the incoming water.

Soon after turning north on a course for Holland, a small section of the water tight wall started to leak and the marine contractors knew that they would probably lose the vessel. Fighting to keep the last main pump operational, John Bultema II, then only 20 years old and working as a diver for his father’s company, lost the battle to the incoming water.

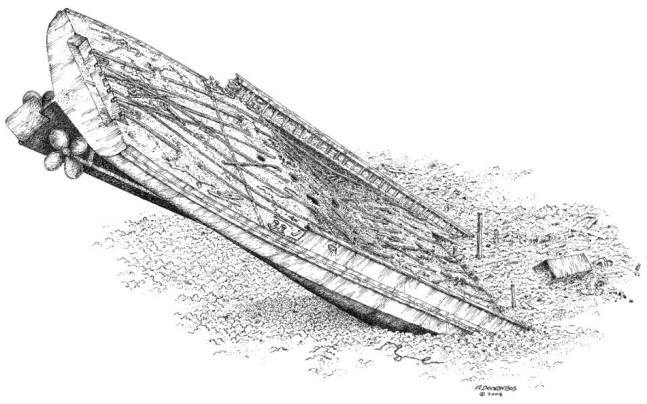

Bultema was plucked off the sinking hulk by a crane just seconds before the barge rose up stern first and plunged to the bottom of the lake in 160 feet of water. The men aboard the tug watched as the churning and frothing waters sucked the ship down. Some say they actually heard the concussion as it hit bottom. It plunged like a spear at the break point where water flooded in, and impaled itself in the bottom where it still rests precariously four decades later. Once back at their company headquarters in Manistee, Michigan, Bultema Jr. reported the loss of the barge to his father, John Bultema Sr., whose reaction was only relief that no one had been injured or perished in the accident.

MSRA is convinced the marine chart designation “Wreck PA” or “Wreck-Position Approximate,” located just off South Haven, Michigan is the location where the stern section of the AA5 was thought to have been left behind. Bultema issued a notice to mariners to inform authorities of the loss of the ship, but likely was not able to record accurate coordinates in the flurry of activity as the ship careened to the bottom. We now know that this hulk is four miles north and west from the marker on the charts.

In May 2005, during the search for Northwest Airlines Flight 2501, MSRA, along with Clive Cussler’s NUMA organization, located the wreckage of the Ann Arbor no. 5 jutting out of the bottom of Lake Michigan at a 30 degree angle in 156 feet of water.

MSRA and NUMA’s Ralph Wilbanks and Steve Howard captured a side scan sonar image clearly showing the railcar tracks on the deck. The severe angle of the wreck is indicated by the “shadow” alongside the wreck. The front of the stern section as cut away from the bow is plunged into the bottom of the lake and continues for some distance beneath the sand and clay. The length of the wreck from the clay/sand bottom up to the tip of the stern is just over 100 feet.

This wreck reportedly was discovered in the 1970’s by Captain Richard Race during his search for the remains of Flight 2501. The location was never released to the public and only one or two others ever knew of the find.

The Ann Arbor No. 5 is in deep water, approximately 163 feet to the bottom. The vessel’s twin propellers, measuring 12′ 6″ across, and the huge rudder are accessible at about 125 feet. Divers must remember that as they swim forward from the stern, they are also descending rapidly toward the bottom. It is very easy to find oneself in 160 feet of water without realizing it.