N 42° 27.645′, W 086° 31.783′, 230 feet deep

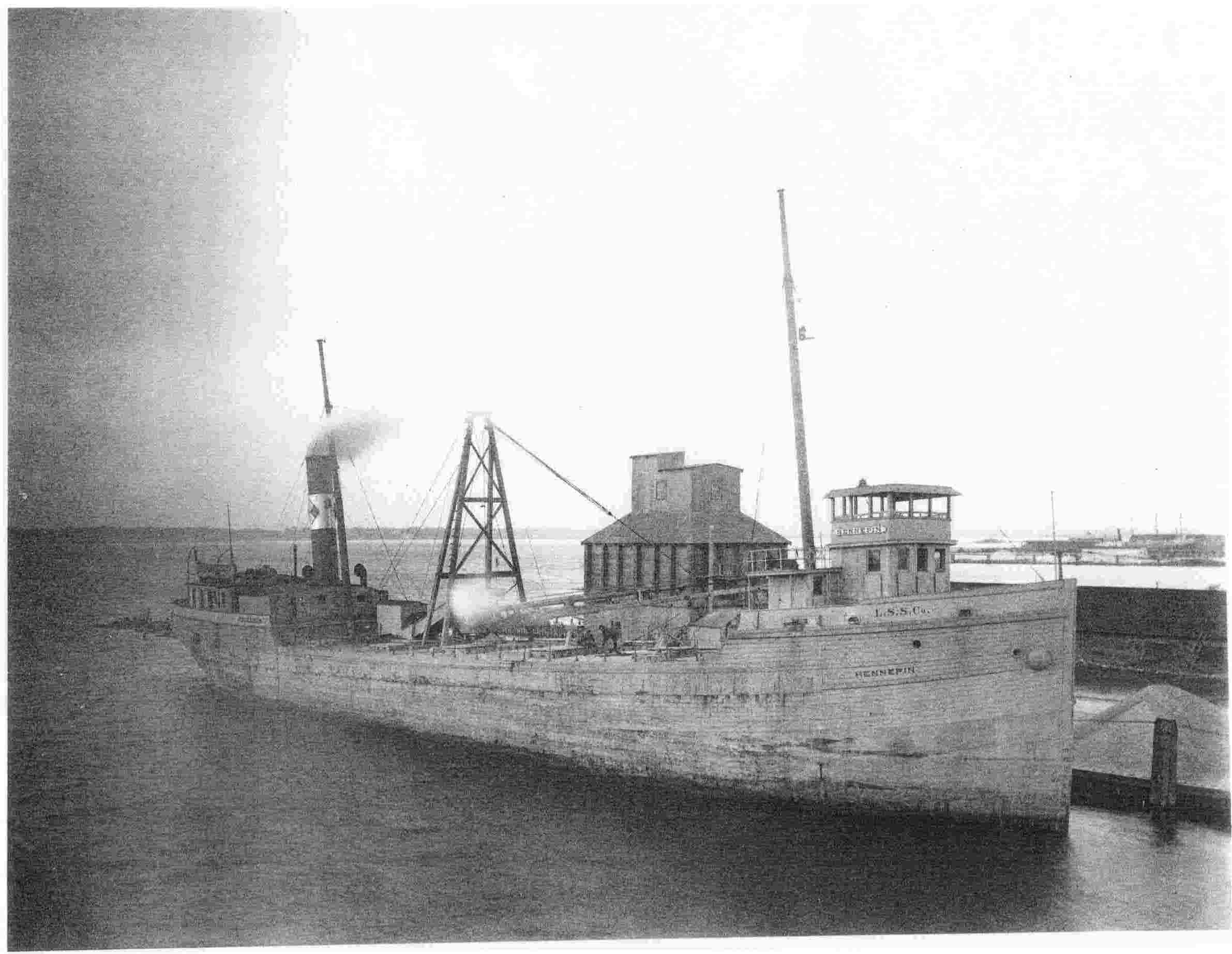

Today’s dominant Great Lakes vessels, the self-unloaders, are modeled after the world’s first self-unloading steamer, the Hennepin, recently located on the bottom of Lake Michigan.

On the sultry evening of August 18th, 1927 the 40-foot tugboat Lotus headed slowly up the Grand River returning to the home port of Construction Materials Corporation in Ferrysburg, Michigan. The tug had departed from this port the day before, bound for Chicago, towing the self-unloading vessel Hennepin loaded with a cargo of crushed stone.

Captain Anderson blew the steam whistle to get the attention of workers near the dock. It was clear something was very wrong There were more crew onboard the tugboat than the Lotus had gotten underway with, and the Hennepin was nowhere in sight. Workers were anxious — where was their ship?

As the Lotus neared the dock they could see the familiar faces of the crew of the Hennepin and her captain Ole Hansen, so they knew everyone was safe, but where was the Hennepin? Realizing their concern, Hansen shouted across the water to explain what had happened. “We lost her boys — she died a hard death”.

Nearly eight decades after the sinking of the Hennepin, Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates (MSRA) set out to find the ship that Captain Hansen helplessly watched sink slowly into Lake Michigan off South Haven back in 1927. MSRA leadership felt that the discovery of the Hennepin would highlight the important roots of the bulk cargo transport industry, which was revolutionized when the Hennepin was retro-fitted as a self-unloader in 1902.

They also knew that finding the Hennepin, unlike other vessels lost in more mysterious circumstances, would be a simple matter of searching exactly where Captain Hansen reported he lost his ship.

In 2005 after three seasons of searching, MSRA finally located the wreck of the SS Michigan. In hindsight, it was right where the captain reported the loss: 15 to 20 miles offshore in 275’ to 300’ of water. And because of that discovery, MSRA learned to trust the accounts of survivors, particularly a seasoned lake captain. Captain Hansen reported that the Hennepin sank off South Haven in 203’ of water. It seemed odd that the depth would be so specific, but trusting the Captain’s account, MSRA developed a probable search area based upon that depth range.

The 214’ Hennepin was built by Milwaukee’s Wolf and Davidson shipyard, the largest shipbuilder in the region, and launched in October 1888. The steamer was originally named the George H. Dyer, in recognition of William Wolf’s son-in-law. Originally fitted with three masts and the salvaged engine from the steamer William T. Graves, lost off North Manitou Island in 1885, the Dyer was built for hauling cargo. With a 1600 ton single cargo compartment, and a value of $85,000, the Dyer was rated A-1 at the time of her building.

The Dyer would change hands many times in her life, several in the first decade. At 10 years old she was sold to a Michigan partnership to transport package freight for the SOO Line Railroad through the Great Lakes from Buffalo, New York to Gladstone in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The ship was renamed Hennepin, after French explorer, Father Hennepin, who voyaged with Robert Sieur de LaSalle through the Great Lakes in a 1679 expedition. Perhaps that name was chosen because the Hennepin would run shipments through Lakes Erie, Huron and Michigan following the same route that La Salle and Hennepin traveled, over 200 years earlier on the vessel Le Griffon.

On June 27, 1901, while loading at her dock in Buffalo, the Hennepin caught fire from an adjacent freight house which was in flames. Her upper works burned and her machinery was ruined, resulting in over $30,000 in damage. Were it not for this fire, the Hennepin may have drifted into obscurity. Instead, she was resurrected, repaired and converted into what would be the world’s first self-unloading steamer. Simply put, the Hennepin is one of the most significant vessels ever to sail the Great Lakes for one indisputable reason: her 1902 conversion provided the model upon which virtually all future self-unloading bulk vessels, on both fresh and salt water, would be based.

After the fire, which nearly destroyed the Hennepin, entrepreneur Frank Merrill bought the hulk from the underwriters for $18,000. Merrilll had just formed the Lakeshore Stone Co. for the purposes of mining the shallow limestone deposits found near the shores of Lake Michigan, east of Belgium, Wisconsin. Merrill hired Chicago’s Webster Engineering Company to design a state-of- the-art quarrying operation complete with a pier into Lake Michigan for loading stone. To transport the quarry’s output, Webster engineered an unloading system to be installed on the Hennepin. The Milwaukee Dry Dock Co., a consolidation of Wolf and Davidson, the original builders of the ship, fabricated and installed Webster’s unloading system on the Hennepin.

Inclined walls within the hold dispensed cargo onto conveyors below deck which ran the length of the ship. The conveyors moved the cargo into a hopper where it was transferred to an inclined conveyor, up to the conveyor boom on deck, which swung over to deposit the bulk material on land. What made this advancement completely unique was that the ship would no longer require massive shore infrastructure at major harbors to unload its’ cargo. The Hennepin could discharge its stone not only in a small harbor, but along a river, into a construction caisson, or into trucks, something not possible before this development.

Lakeshore Stone Co. continued in operation until 1920 when competition reduced its revenue. Leathem Smith, whose L. D. Smith Stone Co. was a major competitor of Lakeshore, chartered the Hennepin to carry crushed stone from his newly enlarged quarry just north of Sturgeon Bay Wisconsin. He would use the Hennepin for the next three seasons which was likely the inspiration for his own improved self-unloading system. In 1923 Smith bought and converted the 31-year old, semi whaleback Andaste into a self- unloader using his design which became known as the “Leathem D. Smith Patented Tunnel Scraper Self-Unloading System.” Blade-like scrapers, rather than conveyor belts, made conversion easier and more economical and allowed more flexibility in the types of cargoes that could be hauled.

Smith returned the Hennepin to Lakeshore Stone Co. in 1923 and they sold it to Construction Materials Corp., a Chicago company founded in 1907. While the ship was old and tired, its unloading equipment made it valuable to a company which had just purchased 1,100 acres of property several miles up the Grand River from Grand Haven, Michigan. The property contained vast deposits of stone ready to be mined and the Hennepin would be used to haul the aggregate. (Today the quarry has filled with water and is the site of the Bass River Recreational Area in Ottawa County.)

After being quarried, stone was brought down the Grand River to Ferrysburg, Michigan where it was sorted into different sized gravel and rock, then loaded onto ships and transported to Chicago. Much of the gravel hauled to Chicago on the Hennepin was used as fill, becoming the bed for the Outer Drive, Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and Adler Planetarium.

Since the late 1990s. MSRA has retained the services of David Trotter from Canton Michigan to conduct sidescan survey operations in search of lost ships in Lake Michigan. Keeping detailed records of nearly 200 square miles scanned in eastern Lake Michigan, MSRA knew they had already covered almost half of the Hennepin’s probable search area during prior search expeditions for other lost wrecks, but the steamer had not been discovered. In July 2006 Trotter covered the balance of the Hennepin‘s search area extending east, north and west of areas already covered working in depths ranging from 190’ to 250’. Running lanes in a pattern much like mowing a lawn, the 50 kHz torpedo-like sonar was towed 100’ below the boat sending acoustical signals out to each side. The remaining 25 square mile search area was completed in just four days with no discoveries. Or so it appeared.

To be thorough, MSRA reviewed the rolls of sonar paper to check for any targets that might have been overlooked by the boat crew. As the paper unrolled, an unusual “splotch” appeared. The image, although quite small and rough, suggested a man-made object because it had both density, revealed by the dark plot, and height, indicated by the white shadow. Usually a target like this would be plotted several times on site to obtain more detail, but it had been missed, probably during a crew shift. Meticulous record keeping pinpointed its size and location, but clearly there was not enough detail to determine if it was the Hennepin — only a dive would tell.

The only known account of the Hennepin’s sinking was a news article from the Grand Haven Tribune in which Captain Hanson’s blamed a “stiff Nor’wester” for causing his ship to sink. Obtaining weather records from the National Climatic Data Center from August 18, 1927, MSRA learned that only a moderate breeze was blowing that day. Additional light was shed on the story of the sinking when MSRA discovered an oral history from now deceased Spring Lake Michigan resident and former Hennepin crewmember, Vern VerPlank. VerPlank spoke with several Hennepin crew members who survived the sinking and from his personal recollections (indicated by quotations) the true details of the day are now known.

“On a tow-barge none of the officers had to be licensed. In fact, most of them were ex-licensed, having lost theirs after an accident or due to alcohol abuse.” Ole Hanson may not have been licensed, but could have found employment on the tow-barge Hennepin.

On August 18, 1927 after offloading her cargo of gravel in Chicago, Lotus Captain Albert Anderson directed his crew to secure the hawser that ran from the Hennepin to the tug. With an empty hold, the Hennepin was riding high on her return trip to Grand Haven. “The old hull was taking on water as she typically did and all ten of her bilge pumps were running”.

It was smooth sailing for the first few hours, but around 10:30 a.m. Hansen noticed the pumps weren’t keeping up with the incoming water. “Chief Engineer Abe Lyons, notorious for slacking, must not have kept the pump filters cleaned.” Any attempts to clean the pumps at that point were futile as the water was gaining fast.

By 2:30 p.m. It was clear that Hennepin was not going to make it home. “Abe Lyons grabbed the distress whistle and blew it four or five times to get the tug’s attention. Captain Hansen called out to abandon ship. Ernie Casperson, the cook, took quarters of beef out of the cooler. Lyons went down to the engine room and took off the big brass clock.” They launched the lifeboat in calm seas and rowed away from the Hennepin with no panic or pandemonium.

As the big ship wallowed deeper in the water, the crew of the Lotus finally released the hawser. “Everyone watched as the Hennepin finally sank beneath the waves and the whole galley house floated right up from the ship. The Lotus kept ramming into it to break it up so it would not be a hazard to other ships.”

With nothing to do but wait out the return trip, Hanson must have realized the sinking of the Hennepin, valued at over $100,000, meant a huge loss for the company who still had enormous quantities of gravel to transport to Chicago. He would also have been concerned for his own livelihood, because there were few employment options for unlicensed captains. When the tug reached its home port, Hansen likely invented the tale of the “stiff nor’wester” to shift blame from himself and his crew.

One week after the discovery of the new shipwreck, MSRA’s technical dive team made the first dive to attempt to identify the wreck. It lay in 230’ of water, which was not too far off from the 203’ reported by Captain Hanson. (Perhaps the newspaper reporter accidentally transposed the 3 and 0?) The divers’ tanks were filled with a special blend of gas to reduce the effects of “nitrogen narcosis”, a condition caused by breathing nitrogen under pressure similar to drinking several martinis. The gas, called tri-mix, replaces a percentage of nitrogen with helium, allowing them a clear head at depth.

After a 20 minute dive and a 45 minute decompression, the divers returned with a positive identification of the Hennepin. The side scan had been deceiving; the wreck was in good condition looking much like it had in historical photographs. Tour the wreck with MSRA tech divers:

The visibility was exceptional and nearly 70 feet above the bottom, the wreck could be seen sitting upright on the flat sand bottom in near-perfect condition, evidence of the slowness in which the ship sank. Ambient light penetrated to the bottom.

The 2-story wheelhouse is missing, likely carried away during the sinking, but otherwise the forward deck, called the “forecastle”, remains intact. The tow winch sits in the center of the forward deck, still coiled with the hawser which runs taught through the fair lead at the tip of the bow. From there, the cable curves, gently downward to the bottom where the “bitter end” lies in the sand just as it was cast off by the crew of the Lotus. The capstan, which was used to raise and lower the anchor, sits forward of the tow-winch and bears the engraved name G.H. Dyer on its domed cover. Aft of the capstan, divers saw the ships wheel which had been located in the wheelhouse, now exposed on deck, with every spoke in perfect shape.

Just behind the wheel, the main deck steps down and five cargo hatches are revealed along with the still-standing mainmast, located forward of the first hatch. Behind that, the conveyor boom lays over the hatches down the center of the deck. Only the canvas belt is missing, deteriorated after its long submersion. Looming in the distance is the massive 40-foot tall A-frame standing securely in place with its cable still ready to hoist the boom into position.

Near the stern, is the boiler house. Although the engine had already been removed before the sinking, the boiler, which supplied steam for the unloading equipment, remains intact in the stern, but the smokestack has toppled. The aft mast has also fallen.

The most significant damage is to the stern and starboard hull, portions of which have fallen outward. The broken hull, however, conveniently provides a perfect cutaway view of the inner workings of the conveyor system which runs the length of the hold. It is ironic that the pioneering equipment, which makes the Hennepin such an archaeologically significant ship, is completely intact, while the older hull has deteriorated around it.

The loss of the Hennepin was a great blow to the Construction Materials Corp. With an active quarry operation on the shores of the Bass River, another vessel was needed to carry the thousands of tons of gravel yet to be mined. It was nearly a year before the chartered another self-unloader, the Andaste from the Leathem D. Smith Co. in Sturgeon Bay, to handle their transport needs. The Andaste was equipped with Leathem Smith’s first patented tunnel scraper system, which was inspired by the Hennepin‘s innovative design.

In an ironic twist of fate the Andaste died an even harder and more tragic death than the Hennepin. Just two years after the Hennepin sank, the Andaste — owned by the same company, running the same route, delivering the same cargo, and equipped with a similar prototypical unloading system — was swallowed up just miles from her predecessor. The ship took with her Captain Albert Anderson, who piloted the tug Lotus when the Hennepin sank, and all 28 crew members, many of who crewed on the Hennepin. Tragedy aside, it is truly remarkable that Lake Michigan holds the first two examples of revolutionary developments in bulk cargo transportation within a few miles of each other. Perhaps the Andaste’s final resting place will soon be discovered.

Today self-unloaders, the dominant type of vessel on the Great Lakes, represent a multi-million-dollar bulk cargo industry. They deliver dozens of products like iron ore, coal, and sand to virtually every conceivable destination throughout the Great Lakes still using systems modeled after the very first conveyor belt system fitted on the Hennepin. This historic shipwreck with its ground-breaking equipment is currently on exhibit 230’ beneath Lake Michigan in an extraordinary underwater maritime museum where it serves as a reminder of the roots of an industry still flourishing after more than a century.

Several months after our discovery a St. Joseph resident, who had purchased a lifeboat oar at a garage sale, presented the item to the Heritage Museum where it remains to this day.

- A close up view of the Hennepin oar