44.4944° N x 86.2897° W

The “Baby” Jane: A little wreck, a big story, and a lovely lady

By Valerie van Heest

In 1923, a small Chicago shipbuilder crafted two nearly identical 58-foot steamships and put them on the market. One sold to a nearby Chicago business operator, who named it Jane after his three-year-old toddler. He operated it for only four years before a mishap off Arcadia, Michigan, on May 27, 1927, caused it to sink while carrying a cargo of cement. Years later this shipwreck would find itself in the center of, not one, but two controversies, and would lead me and my associates from the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association to dive the wreck, and reveal its true history.

A controversial shipwreck discovery in 1994

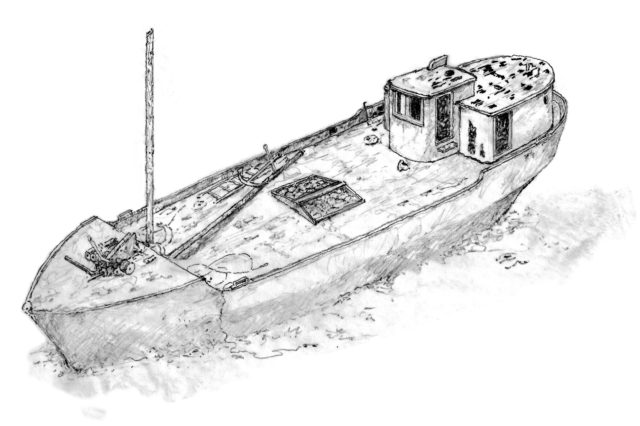

The Jane became known to the dive community in 1999 when Michigan diver Michael Spears presented a video program about the wreck at several annual symposiums for divers. He explained that surveyors hired by a telephone company to scan the lake bottom before laying telephone cable off Arcadia, Michigan, found the wreck in about 100 feet of water and reported it to Michigan’s state archaeologist, John Halsey. Halsey asked Spears to assemble a team to dive, document, and identify it. Spears’ first dive revealed a shipwreck in near pristine condition. It sat upright on the bottom with its forward cabin, aft pilothouse, and single mast still intact. Its hull and deck were, likewise, in excellent condition and there were several artifacts, including, the ship’s wheel, anchor, and bell. Spears knew that if the location became known, divers might pilfer these artifacts and damage the wreck setting grapple hooks or anchors. He shared his concerns for the wreck with Halsey and began doing research to identify it.

The 1990s were a controversial period in shipwreck diving in the Great Lakes and the Jane served to fuel that controversy. In 1987 President Ronald Reagan had signed into law the “Abandoned Shipwreck Act,” which turned over ownership of the wrecks in state waters to the states in which they lay. In turn each Great Lake state enacted laws that, in essence, made it illegal for divers to recover anything off a wreck without a permit from the state. Most divers did not like the idea of government interfering in their hobby and worried that the states may, in time, make diving on shipwrecks illegal.

Until that time, divers operated on a “finders keepers” rule. If they spent the time, money, and effort to find a wreck, then they considered it their right to recover any artifacts they found interesting. And recover artifacts up they did, often stripping wrecks bare, and sometimes even using explosives to gain entry inside wrecks. Of course that very behavior led to the enactment of laws to protect shipwrecks as recreational and historical resources. But not all divers respected the law, preferring the old ways of finder’s keepers.

As with any new law of a controversial nature, people often react by testing its enforceability. Prohibition is the most obvious example. The 18th Amendment, made law in 1920, prohibited the sale, and consequently lawmakers hoped, the consumption of alcohol. However, those who wanted to drink found ways to drink. People either made alcohol themselves or purchased it from a new crop of spirit manufacturers, distributors, and sellers, willing to break that law; so many that law enforcers could not keep up with them.

Some divers reacted similarly in the wake of the new shipwreck laws. After all, there were no police boats stationed over shipwrecks and very little manpower to investigate reported artifact thefts. At the time of the Jane’s discovery, there were three active court cases in which state governments were suing divers who had blatantly recovered artifacts. But Spears and other preservation-minded divers knew there were still many divers more clandestinely pursuing their pilfering hobbies.

Because John Halsey did not want divers to worry that he was purposely keeping this wreck from them, he and Spears decided to use this wreck as a test case to see if divers, given a new wreck that required no effort on their part to find, would respect the law and maintain the wreck as found for their own enjoyment. Spears publically presented his video of this unusually intact vessel, letting divers know the location would soon be made public and asking them to respect the site. It went without saying that the State of Michigan now had a full inventory of the artifacts that would serve as evidence if they had to prosecute any thefts. Spears called his program about the small steamer “What’s Going to Happen to ‘Baby’ Jane?” a play on the name of an old Bette Davis movie, altered in such a way to remind divers that they were being tested. The state archaeology office never officially released the coordinates to the diving public, but Spears did through a documentary produced by diver Rick Mixter for PBS in 2001. He believes that the wreck is too isolated to have drawn many divers, and so the location was simply forgotten.

Fast forward to December 2016.

Two middle aged, though relatively new divers from Muskegon, Michigan, Kevin Dykstra and Fred Monroe, announced to the media that they had discovered a new shipwreck off Arcadia, Michigan, with a safe on board, that they thought contained gold, silver, and jewelry. I saw the newscast and recognized the wreck as the Jane because I had been in an audience in 1999 when Mike Spears showed his “baby” Jane video. And I recognized the divers from a prior newscast.

In December 2014 they were featured on another local news cast under the headline, “Muskegon divers claim to find elusive Le Griffon shipwreck.” The Griffon, a wooden sailing barque with a reputed figurehead of a griffon, built along the shores of Lake Erie in 1679 under the direction of French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle, sank somewhere in northern Lake Michigan or Huron on its maiden voyage that year. As the first shipwreck on the upper Great lakes, the Griffon has been the most sought after shipwreck, with some two-dozen reported discoveries over the last 300 years, most proven bogus.

This claim was simply the latest in a series of controversial claims. Dykstra and Monroe reported that the Griffon was not even the object of their search. They had discovered it off Frankfort, Michigan, accidently while searching for a “boxcar of Civil War gold, dumped off a carferry, that they heard about through a deathbed confession,” a tale that was immediately debunked by professional Civil War historians. I had heard about their Griffon claim a year before they went public from maritime historian Brendon Baillod, who had been contacted by the Muskegon divers to review their footage and offer a professional opinion about its identity. Baillod pointed out the big boiler surrounded by charred timbers and pronounced the wreck a burned tugboat either of late 18th or early 19th century vintage. But I guess they didn’t believe him. A year later they announced their discovery of the “Griffon” and began pestering Michigan’s current state archaeologist, Wayne Lusardi, to dive the historic wreck.

Because even the most neophyte divers, and certainly an archaeologist, should be able to recognize a boiler, it seems likely that these divers were only pursuing this claim for the media attention, good or bad. In fact, word began traveling among the dive community that the diving duo was trying to get noticed by reality television producers. And what better way than through tales of Civil War gold, the Griffon, and safe filled with treasure? The media eventually goaded Lusardi into diving the wreck and he dubbed it, as Baillod had, a burned tugboat from the late 18th or early 19th century.

Another new controversial shipwreck discovery

The December 2015 newscast showed the treasure hunters’ video of the newly discovered wreck and zoomed in on a rectangular object in the pilot house, about four feet wide, two feet deep, and three feet high, covered with a thin layer of invasive zebra mussels that have, since their introduction onto the lake in the 1990s, been colonizing on shipwrecks. Dykstra pointed it out as the safe and talked of the riches inside.

After the Griffon announcement by these boys who cried wolf, I laughed when I saw the “safe.” I recognized it as the ship’s cast iron, wood-burning stove, a fixture on all vessels of that vintage to cook on and keep warm with. Either these divers were too excited to see the five circular burners and its four legs, just like they had missed the big boiler on the other wreck, or they were manufacturing a story for the media’s consumption. A safe filled with jewels is, certainly, more compelling than a stove filled with waterlogged ashes.

I had been interested in diving the Jane since seeing Mike Spear’s tantalizing video in 1999, and what better time than now, when it was back in the spotlight because of a new controversy over the “safe. I contacted Mike Spears for the coordinates and MSRA divers, Jeff Vos, Todd White, Bob Underhill, Craig Rich, Kevin Ailes, my husband Jack, and I dived the Jane in the summers of 2016 and 2017 to acquire our own footage and to take a close look at the stove.

Acadia, Michigan, is a small, sleepy, one-restaurant, one- gas station town, surrounding the small Lake Arcadia. A channel there leads out to along a pristine stretch of Lake Michigan shoreline in Michigan’s West Michigan. There are no dive charters anywhere near Arcadia, but the full series marina that welcomes transient boaters who better count on sleeping on their boats because the closest motel is 20 miles sway. We were there to dive, not sleep, so once we launched our boat, we headed right to the channel, passing the shallow remains of a schooner that grounded north of the channel a century ago. It took 20 minutes to reach the Jane two miles offshore. The water there is about 102 feet deep. There is no mooring, so we set an anchor in the sand alongside the wreck. But we have the same concerns that Spears and Halsey had back in 1994. The intact wreck could suffer irreparable damage from a stray grapple hook or anchor that could topple the mast or penetrate the now fragile roof of the forecastle or pilothouse.

Acadia, Michigan, is a small, sleepy, one-restaurant, one- gas station town, surrounding the small Lake Arcadia. A channel there leads out to along a pristine stretch of Lake Michigan shoreline in Michigan’s West Michigan. There are no dive charters anywhere near Arcadia, but the full series marina that welcomes transient boaters who better count on sleeping on their boats because the closest motel is 20 miles sway. We were there to dive, not sleep, so once we launched our boat, we headed right to the channel, passing the shallow remains of a schooner that grounded north of the channel a century ago. It took 20 minutes to reach the Jane two miles offshore. The water there is about 102 feet deep. There is no mooring, so we set an anchor in the sand alongside the wreck. But we have the same concerns that Spears and Halsey had back in 1994. The intact wreck could suffer irreparable damage from a stray grapple hook or anchor that could topple the mast or penetrate the now fragile roof of the forecastle or pilothouse.

We knew that the visibility is generally good in the area because there is no industry to discharge effluent, and the mussels are still keeping the water clean, so we set our anchor about 30 feet off the wreck. Heading down the line, we spotted the Jane when we reached the 40 foot mark, let go of the down line, and glided over to the tip of the forward mast. From there we could see the entire wreck, bow to stern, just like in the clear, blue waters of the ocean. After 20 years since Mike Spears first filmed the wreck, the decking over the roof framing of the pilothouse has decayed, but everything else looks much the same.

We examined the winch at the bow, and then peered into the forecastle where we saw the frames of two bunk beds, the mattresses long decayed. Then we headed aft. The fallen boom, a ladder, and steel stock anchor rest gently on the amidships deck and we could see the ship’s bell lying on its side at the base of the pilothouse where it had fallen off its roof mount. The center hatch, through which the cargo would have been loaded appears filled to the brim, presumably with its last cargo, cement.

The pilothouse beckoned us, and we swam right in through the open door posing for a moment in front of the wheel for a glamour shot. And as we swiveled around, we saw the stove, looking still very much like a stove despite the zebra and quagga mussel buildup.

We spent the rest of our 25-minute dive hovering about 20 feet off the wreck, feeling like a bird in flight must feel, just marveling at how beautiful and intact the wreck is.

After the dive we wanted to learn more about the career of the “baby” Jane and the accident that sent it to the bottom of Lake Michigan. I turned to my business partner William Lafferty, an award winning maritime historian, museum curator, and author with a knack for researching shipwrecks.

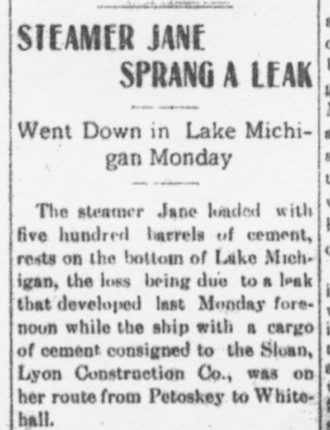

He did some digging and learned that this vessel had been built in Chicago in 1923 by a shipbuilder Hebert N. Heath. A businessman, Urban F. Myers, operating a nearby salvage company, purchased the vessel initially to expand into the salvage of sunken ships and their cargoes. He named it for his three-year-old Jane. He only operated it for four years until in May 1927 he leased it out to Captain John Roen to carry cement from Petoskey to Muskegon for use in a new road projects.

The Jane began leaking as it approached Arcadia on May 30, and though the captain and 2-man crew tried to staunch the flow, the ship started going down. All three men made it off the Jane and into the ship’s small boat and rowed to shore about three miles distant.

The Jane began leaking as it approached Arcadia on May 30, and though the captain and 2-man crew tried to staunch the flow, the ship started going down. All three men made it off the Jane and into the ship’s small boat and rowed to shore about three miles distant.

The most exciting thing for me in this project was learning that Bill Lafferty had found Jane. No, he’s not claiming to have found the wreck too. He found the real “baby” Jane, the toddler who was three years old in 1923 when her father purchased and named the steamship after her. She is alive and well at the time of this article’s writing, living on her own in Arizona at 98 years old. She is the treasure!

The diving duo from Muskegon has found their treasure too. History Chanel signed them up for a “reality” show called “Curse of the Civil War Gold, a show had been so ardently campaigning for since their media-attention-grabbing Griffon claim in 2014. The “curse” is theirs alone: they have lost all credibility. And the “gold,” we can surmise, is just a red herring like their “Griffon” and their “safe.” As the saying goes, “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.” But mostly, shame on the History Channel for duping viewers who expect actual history.