Since 2004, Michigan Shipwreck Research Association has searched the waters off South Haven, Michigan with Clive Cussler and his team from the non-profit National Underwater Marine Agency looking for the remains of Northwest Airlines Flight 2501, a DC-4 airliner lost in 1950, killing 58 people. At the time it represented the country’s largest aviation disaster.

Clive Cussler (center), Ralph Wilbanks (right), Jim Lesto (left) and Steve Howard (rear)

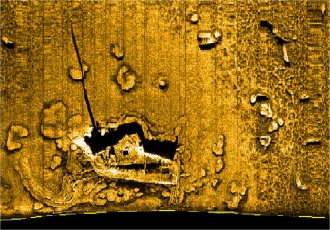

While searching for the plane in 2011, side scan sonar expert Ralph Wilbanks came across a wreck in 250 feet of water that we could never have anticipated finding.

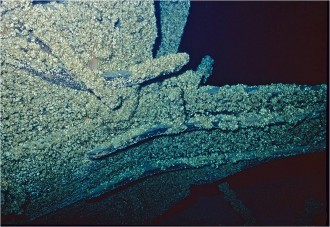

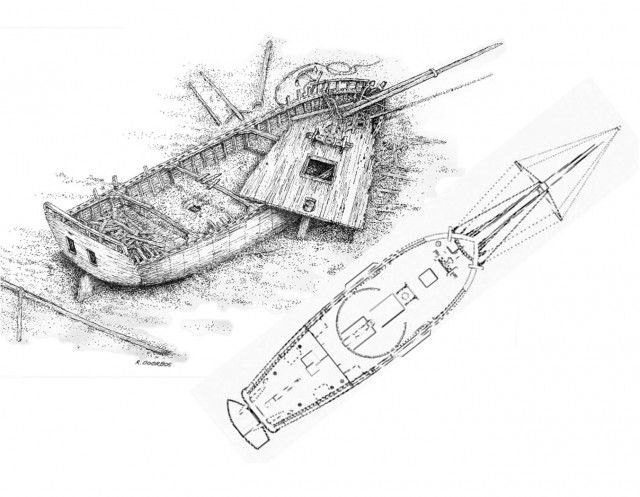

The side scan revealed a small sailing vessel, perhaps with an intact bow sprit. The sidescan images hinted at a tall stern and a displaced deck.

We weren’t aware of any small vessels gone missing in that vicinity and hoped that sending our technical dive team to the wreck might reveal some clues as to its identity.

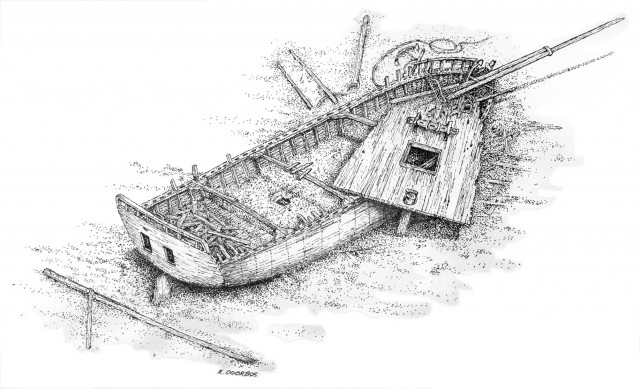

Our technical diving team of Todd White, Tim Marr, Jeff Vos and Bob Underhill geared up for this difficult dive. What they discovered and documented with still photography and video was what appeared to be an early nineteenth century merchant sloop.

They encountered a rare scroll bow, a fallen bow sprit, and a large center cargo hatch but no cargo. The aft cabin was missing . The tall rear bulkhead was still on place and still showed a pair of dead lights, or small windows, which suggest passenger and crew cabins. The vessel had no centerboard and showed indications that it was tiller-steered. There is a fallen mast near the stern and an anchor chain off to the starboard side. The wreck was measured at 47 feet long and about 17 feet wide.

Take a video tour of this wreck:

Positively identifying this sloop has been difficult. Of the few sloops known to have disappeared in Lake Michigan, the Spitfire and Sun both registered at 50 feet remain possibilities. The Spitfire was lost in 1841 and the Sun in 1847, both on Lake Michigan. However, there are no records that either had a scroll bow, a significant feature of the wreck.

The measurements of the wreck do, however, match the documentation of a sloop called the Buffalo which was built—appropriately—at New Buffalo, Michigan in 1845 for the cost of $1000. At a registered size of 49 feet by 16 feet, the dimensions are within a foot of the size of the wreck as measured by the divers. The extra may well be explained by sagging occurring over 160 years underwater.

Most notably, the Buffalo‘s enrollment indicates it had a scroll head. However, we are taking quite a leap in this potential identification because we couldn’t find any records of this sloop’s actual loss on Lake Michigan.

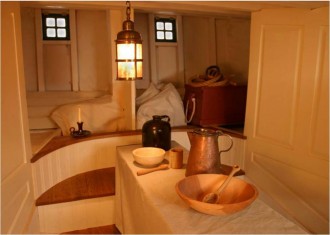

A New York newspaper indicates the Buffalo was built by Amos Johnson of New Buffalo and launched on Saturday, June 21, 1845. It noted the vessel as a staunch and well built craft, fitted up with a new and convenient cabin, with berths for passengers. The Buffalo served the passenger trade between New Buffalo, Michigan, and Chicago.

The last enrollment document, dated 1849, indicates that the Buffalo was then owned and mastered by William London. It was surrendered in 1850, signed by James Breck, Jr., the Deputy Customs Collector in Chicago. Typically a surrender document would note changes in names, owners or rig, or if it had been wrecked or went missing. 160 years later, Breck’s omission stymies our efforts at identification 160 years later.

A study of the wreck’s deck layout indicates that although missing, it would have had a significant size aft cabin. The presence of two dead lights, or windows, in the stern confirms the passenger cabin because cargo vessels wouldn’t have needed windows.

Coincidentally, its size and design is very similar to the replica sloop Friends Good Will, which was built on the plans of an 1811 merchant sloop. The wreck, however, has slightly larger aft accommodations as would be expected of an exclusive passenger vessel.

By comparing it to the Friends Good Will’s cabin. We can even picture how the cabin on the wreck may have looked. (Click on either image for a thumbnail that you may enlarge.)

Many of these early, small vessels lasted just a few years before being lost or wrecked in the strong surf along shore. Newspapers were few and records dating back more than 150 years can be scarce. However, just because no record of its sinking could be found, does NOT mean it didn’t sink.

Ironically, the Friends Good Will probably frequently sails right over the remains of the wreck we believe to be the New Buffalo.