N 42° 30.454′, W 086° 15.737′, 50′ deep

Early in the summer of 1995, two shipwreck hunters were in southeastern Lake Michigan hunting for a shipwreck, but what they were to find would not be what they were looking for. For the past seven years they had been searching for the elusive shipwreck of the steamer Chicora off South Haven. There are several mysteries off South Haven and the Chicora was the biggest one of them.

Local diver Tom Tanzos, a Michigan State Police officer who had been searching for the Chicora for many years, recalled how taking a break from the Chicora search turned up an unexpected discovery — the wreck of the luxury yacht Verano.

Tom recalled how it started. “At one of our Southwest Michigan Underwater Preserve meetings, Bernie Harris had brought in some videotape that he’d shot of the clay banks north of town. They were rather unique formations, and my Friend Butch Trowbridge and I thought we’d go up there and just check them out for a fun dive, to take a break in our normal activities.”

“Butch located a shiny piece of metal on the bottom, which we didn’t have any idea what it was, but it did have a manufacturer’s tag on it from Cutler-Hammer. So we copied down the name and the serial number, and he inquired with the company, which is still in existence, and they came back verifying it as being part of an electrical rheostat for marine use.

Butch Trowbridge recalled, “And that’s what spiked our interest, and that’s the reason we continued to go back out basically for half of the summer.” Tom Tanzos added “We had shown it to Jim Bradley who’s an avid boater and also an electrician. He identified it as being some sort of an electrical part. We told him where we found it, and at the same time he advised us that he had bought title to a yacht called the Verano, back in the 50’s for salvage purposes, and he had never been able to locate it.”

Butch Trowbridge recalled, “It was Tom’s birthday, August 29th, the kind of a day that religiously every year we’re out diving for the whole day. And that was another one of those days. And it was a beautiful day, good visibility in the lake. And after about a half hour of searching, we were all in different directions from the boat. We had all got low on air and had surfaced, and when we came up, we, of course, yelled at one another and hollered at one another that, ‘I found it”.

What these divers found was the long forgotten luxury yacht Verano. In discovering this wreck, these divers opened a porthole to the past, rediscovered an era that has almost been forgotten and set began solving a mystery that has lingered since that fateful day in 1946 when the Verano disappeared beneath the lake.

The year was 1925. This was the “Jazz Age. Personal incomes were high. The “nouveau rich,” had plenty to spend on leisure-time activities. Those who could afford it, wanted their own personal yachts. Feeding the desire was New York’s Consolidated Shipbuilding Corporation This yard was the premier builder of large, powerful and luxurious wooden craft, built by fine craftsmen.

Into the shipyard one day came George M. Brown from Greenwich, Connecticut, a wealthy manufacturer of asphalt roofing materials. Among other things, Brown coined the name “Texaco”. He contracted for one of the biggest and best yachts to come out of Consolidated Shipyards, the 92 foot, 69 ton, twin-engine powered yacht he named the Idler. Mr. Brown wanted a yacht to transport himself and his associates in style up and down the coast of Long Island Sound.

1929! The stock market crashed. The nation sank into economic depression. And in 1934, George Brown decided to sell the yacht. Reese Hatchitt, a stock broker from Long Island, New York, purchased it. He renamed it the Paulo Reese II. These were risky times for a stockbroker to own a luxury yacht. In less than a year’s time, the Paulo Reese II was for sale, and ready to embark on new adventures in the Great Lakes. It was sold to Charles Davis, Sr.

At the time of the purchase of the yacht, Charles Davis Sr. was president of Borg-Warner Corporation. Even at the height of the depression, for industrialists like the Davis’s, life was very good. Charles Davis Jr., his son, recalls family life. “They didn’t own securities on the big board or on the market. They didn’t speculate in stocks. And they sailed through the depression without any problem. Because even though the manufacturing businesses they had were declining in sales, there still was enough for the owners to be able to weather the depression without even feeling it.”

Charles Davis Jr. has been an avid sailor and boater all his life, along with the rest of his family. One day, in his youth he came upon some exciting news. “I was out sailing in my sailing canoe, and I was out about 5 or 6 miles in Grand Traverse Bay, and I looked up and saw this cloud of canvass coming, wing on wing, from Charlevoix. And I laid a course to intercept. There was only one man on board, and it was Ernie Wingard, you know, and I hailed him and I said, “Where are you bound?” And he said “I am takin’ this boat, to the Davis’ dock there, in Northport Point.”

This was good news for Charlie. His dad had bought a sailing yacht called the Malibar VI. Ernest Wingard was the captain that day and would later serve as captain of the Verano. A very capable sailor, Charles Wingard is a current resident of Holland, Michigan. Wingard’s son recalled, “He was much more than just a captain on the boat. He was a very good friend of the Davis’. He had a lot to do with spending a lot of time with Charles and Johnson Davis, the two boys , and helping raise them.”

After four years the senior Davis decided to sell the Malibar VI and purchase a luxury motor yacht. Charles Jr. was a young man in college at that time in 1934. “My dad was on the phone. He told me he bought a boat. And I said, what kind of a boat? And he said a yacht. How big? Ninety-one feet. And so, you know, this was a big surprise because there’s a big difference between 90 feet and 50 feet, which was the schooner. And I knew that the schooner was going to be sold anyway, he had told me that sooner. And that was not welcome news but the purchase of this big yacht was exciting. And he told me that he wanted me to go down and survey the boat. He had bought it sight unseen from a man who had lost all his money in the stock market.”

The Paulo Reese II was renamed the “Verano,” which was Spanish for summer. It was a type of yacht that, in those days, required a full crew just to operate it. The engines were operated from the engine room by messages telegraphed from the bridge. Charles Davis Jr. said, “You have to realize that in those days we didn’t have the navigation equipment that you have today. We had no radio — no radio at all. We had a compass, a protractor, a lead line, and a chart case with charts, and that was it. And you did all your dead reckoning and piloting with those instruments. The gas tanks carried 800 gallons per tank, or something like that. And that’s 1,600 gallons of gas.— And in those days you didn’t have marinas where you could duck in and get loaded with gas in the marina. When you get to a dock, which is usually a coal dock or something, we would have to call an oil company and get a tank wagon down there and buy a tank wagon price.”

After inspecting the yacht, the next step was to moving it from New York to their private dock at Northport Point on the upper shore of Lake Michigan. Charles Davis Jr remembered, “We brought the boat from New York through the Erie Canal up into Oswego, up into Lake Ontario, and then to the Welland Canal and then down to Lake Erie, crossed the length of Lake Erie into the Detroit River, and stopped at the Detroit Yacht Club.”

The voyage continued through Lake Huron, into Lake Michigan and on to Northport Point. The Verano saw many years of service to the Davis family and friends, transporting them around the waters of the Great Lakes. It stayed with the family through the depression and almost into the war years. The Verano also played a prominent role in the business of Jesiek’s shipyard, today known as Eldean’s, in Holland, Michigan. As a growing business it recognized the need to store yachts and commercial boats the size of the Verano for the winter season. There being no facilities on either side of the lake, the Jesiek brothers, with encouragement from the Davis family, built the first marine railway that could haul out of the water boats with a length up to 110 feet. It was here the Verano spent many winters, and it was to this yard the Verano was headed on its final voyage in 1946.

Just prior to the war years the Verano was sold to J. Robert Baumgartner, the wealthy owner of Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s, Reliable Tool and Machine Works. World War II was an infamous time both for the country and the yacht. Several times it was in the news. During the war, restrictions had been placed on travel, and basic commodities such as gasoline, were being rationed. Despite that, in 1944 Baumgartner motored his yacht across the lake to Saugatauk, Michigan. The port of Milwaukee accused him of taking the yacht out of their jurisdiction without permission and an armed guard escorted the yacht back. The office of price administration accused Baumagartner of violating gasoline rationing regulations and prohibited him from using either his yacht or his automobile for the duration of the war. The Verano languished for two years.

In May of 1946 a new owner, mister Maynard Dowell, owner of the Aero Dusters Company of Chicago, purchased the yacht and docked it at the Chicago Yacht Club basin. Its value was then $75,000. Three months later, on August 28th, in bad need of overhaul and repainting, Dowell decided to move it to the only place that could repair a boat of this size, Jesiek’s boat yard in Holland, Michigan. His intention was to have it ready in the fall for a trip down the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico.

Aboard were three men, Chester Granath, an engineering associate of Dowell’s, Fred Stenning, also an engineer, and Ben Murasaki, a cook. The trip would take them from Chicago, Illinois to Holland, Michigan – 90 miles as the crow flies. None of these men had much experience with the Verano. Jesiek’s boat yard had not seen the Verano since before the war, and, as it turned out would never see it again. The yacht never arrived.

On the day that Tom Tanzos, Butch Trowbridge, Butch’s son Andy and his friend Kevin re-discovered the wreck of the Verano, they were elated. Butch was sure that this was it. “It stood out like a sore thumb there on the bottom. And also when I swam up closer I saw what it was. On top of this anchor windlass was another one of these variable rheostats for running the electric motor for the windlass. So I swam over and wiped the data tag off, and that was the same data tag as the piece we’d found initially. And so I knew that the first piece that we had found came from the Verano.” Said Andy, “It was really exciting to be diving on something that no one else had seen for so long. And to be able to do that when you’re sixteen years old, to see something that nobody else has for 48 years or whatever, it is just really exciting.”

In the days that followed, excitement gave way to questions. Though the yacht had lay on the bottom for a relatively short time, there was little left of it, Why is it so scattered and missing? What happened that fateful day? Why did it sink so close to shore? They called upon Ken Pott, then curator of the Michigan Maritime Museum in South Haven for help.

According to Pott, “There was a great deal of research that was necessary to determine the history of the yacht Verano and the people in American history who were associated with the vessel in this period in time. We went to local and regional and national archives to conduct that research from the Great Lakes region to the East Coast where the Verano was built, and basically, over time, reconstructed its history and its importance in maritime tradition in this country.”

In researching the history of the vessel, mysterious circumstances surrounding the sinking came to light. The seas were relatively calm. The U. S. Coast Guard reached the Verano just minutes before the vessel sank below the surface, but no one was aboard and the life boat was missing . A few days later, the lifeboat was found upside down and with the oars locked into the stowed position. Soon after that, the bodies of the three crew members washed ashore and each had his life jacket on backward .

Speculation was rampant in those days immediately following World War II that foul play was possible when it was discovered the cook was Japanese. In addition, the salvage team that dove the wreck days after it went down, found the keys in the ignition and a chair jammed in the wheel as if to keep it on coarse. When the cook’s body washed up on shore, those rumors were proved false.

Over 50 years had passed since the Verano went down and only two options remained to gather clues to the cause of the sinking – to visit the wreck site and talk with people alive at the time.

One thing working in their favor was the relatively young nature of this particular shipwreck. It hadn’t yet become lost in time. Ken Pott said, “There are quite a number of people in West Michigan who were associated with the Verano over time, and we were able to track down a number of them who were still living. They included everyone from vessel owners to men who served as engineers aboard the ship to people who were involved with its repair and maintenance over time and people who were just travelers aboard as well.”

One of the people contacted was a man who actually saw the yacht sink and tried to rescue the crew. Retired Coast Guardsman Bill Herbst recalls, “We got a call at the South Haven station from some people along the beach. In those days most of the cottage people had spyglasses and long-glasses, and they watched everything out there. And the man informed us that he thought that one of our fishing tugs out of South Haven might be in trouble, because he had been in the same position for quite awhile and didn’t seem to be moving. He thought probably they were hooked in their net. Of course when we got in the area, we could see that it wasn’t any fishing tug, and the closer we got we could see that we had a fairly good sized yacht. Then in the process of getting up to her, we could see she was wallowing in the sea. Then we could see that one of the life boats had been lowered — there was two.”

He continued, “And I couldn’t put anybody on the boat to see if there was any crew members or any passengers aboard, because she was so low in the water, and we didn’t know what was causing her to take on water. I still don’t know what caused her to take on water. But anyway she started to sink, and then started to sink real fast. Of course the first thing we did after she went down was I buoyed the position and marked it on the chart. And because the life-boat had been lowered we assumed that the people who were on the boat, at least some of them, had got off. Then we notified everybody. One airplane that was overhead, a passenger plane, circled a couple times, and then took off. Then we alerted everybody and notified the district, which was in Cleveland, and then came back and got ready for an extensive search. We notified all the coast guard stations”.

A massive search found little, only a foundering lifeboat with the oars in place, as if it had been abandoned. Finally, four days later, two of the bodies, and then later a third, washed ashore. Within days of the discovery of the bodies, a salvage diver was sent out to survey the wreckage. Herbst recalls, “I knew Don Cluchy who was a diver and a salvage man. And when the Insurance company wanted to get a look at the boat — they were going to try to pick it up — so they got Cluchy with his barge and his crane. Don Cluchy happens to be a hard-hat diver from the north of here. And they came down and moored by the station, then went out to try to pick it up. And of course, obviously, the weight of the water and the weight of the sand, the rigging that they designed didn’t function, it just cut the boat in half , so to speak. The bow came off first, I think. We always felt that instead of using cable and chain they should have used straps, canvas straps, and put them under the boat and then straighten it out first and then see what he could have done. He never got her up.”

Keeping in mind Bill Herbst’s description of the unsuccessful salvage attempt, members of the Southwest Michigan Underwater Preserve Committee, now the Board of Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates, and a sister organization the Underwater Archaeological Society of Chicago, set out to survey the remains of the yacht.

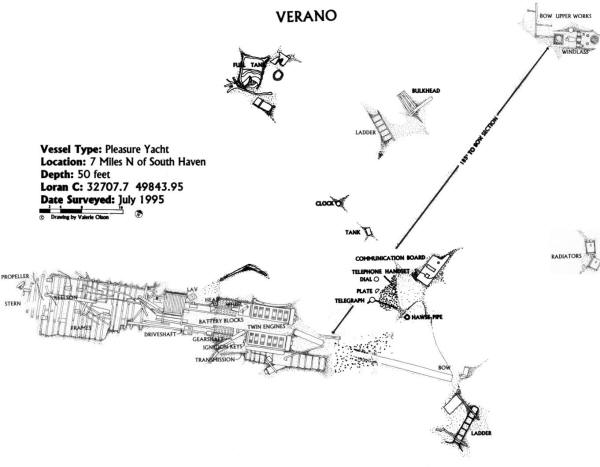

A 7 mile boat ride north out of South Haven harbor brought them to the site of the wreck only 3 miles from shore. The wreck lies 50 feet below the surface. Their goal—to survey the remains and create a site map of how the wreck is situated on the bottom.

The wreck site today leaves few clues pointing to the cause of the sinking due to the damage caused by the attempted salvage. You can see by the completed site survey drawing that the remains are scattered and broken. Preserve members returned to Bill Herbst to gather his thoughts as to the mysteries surrounding the sinking.

Herbst said, “We called in special investigators because of the body that they picked up in Glenn. One of the first ones had his life jacket on backwards. So we called our intelligence service to see if they wanted to go any place with it, to see if there was any foul play, because the boat had just been purchased and had a big insurance policy out on it. There was a lot of ramifications. And of course, In the Coast Guard, we always try to get to the bottom of what’s going on and see what happened. And as it turned out I guess they all met the same fate, and eventually they all got picked up.”

No foul play. Case closed. But the questions still remained. Why did the Verano sink? Charles Davis Jr. remembered the yacht had a strange tendency, “The metacentric figure was not very great. And therefore the boat would roll slowly and have a tendency to remain over there. The righting moment wouldn’t be very great. And the first time across the lake I found that out. Scary.— we know now why she got into trouble when she got a little water in her. Because the water would drag her stern down. It would move with the roll and prevent her from righting herself.”

One day the Davises were traveling easterly in the north channel of Lake Huron toward the Canadian town of Little Current when the rough weather put them in jeopardy. Charles Davis recalls, “They broached, and she lay over on her side almost at 60-degree angle. And all the furniture and everything went over to one side. I’ve always wondered why no one went overboard. There were rails, of course, to keep them aboard. But Ernie was up forward, and Victor was at the wheel when this happened. My Father described it as Victor zigged when he should have zagged. That was his sense of humor. But anyway, Ernie had to crawl out of the forecastle hatch, and actually climb on to the top side of the boat, and drag himself up to the bridge, and then get on the bridge. Victor was in a panic, he didn’t know what to do. Ernie I think put one engine in reverse and Victor went down in the engine room. They put one engine In reverse and one engine forward, opposite to the side they were on, and brought the stern back around. They probably brought the stern around down wind, the bow upwind, and they finally got her back up, back on her course and everything. But I think that incident, my dad probably made the decision, ‘I’m getting rid of this boat.’ He probably didn’t have any confidence in her after that.”

Herbst said, “I would have to think that the fact that she was going down by the stern would be that she was leaking through the stuffing box or something, and they didn’t know it.”

In a round table discussion, former crew member Ike Hagen had a different theory of the leak. “It always leaked. But I don’t know if it was in the garboard strakes. There’s another source Of the leak. The exhaust pipes. Well, I don’t know if it was salt water or what, but there were — the engineer went to fix it, patch it one day. We didn’t know what he was doing. He told us afterwards. Get holes in the exhaust pipe, and he’d patch — get down under the floorboards, you know, and patch it. So we never thought anything about it, except that Grant and I would have to go down the lazaret (storage space between the decks of a ship) and bail it out with buckets sometimes. That could have been a good source of water. That’s what you’re after? Iit didn’t have a crew, number one. There were three guys, and one was a cook. What could one man do with launching a boat or something?”

Ernie Wingard, the former captain, probably was the most correct in assessing the situation as recalled by Charlie Davis Jr., “I think I remember about what Ernie told me about it. He said that the boat was leaking in the Garboard strakes at that time, and he reminded me that that was an ongoing problem with us when we had the boat, that they had to keep the correcting, movement of the planking, and I thnk they call them strakes, and carved-out planking, down near the keel, in after section of the boat. Why it would develop that way, I don’t Know. A matter of vibration maybe. But anyway, he did say that the boat was leaking and she was probably down by the stern, and they got into a storm, the following sea, and she broached, he thought, he said he thought she broached and they probably hit the panic button and they didn’t realize the boat wouldn’t sink in two minutes. Or they thought she was going down fast, and they tried to get away, and since the boat was not in low of keel, keeled over, they couldn’t get the boats out of the davits without capsizing the boat. And he thought what Happened was, that in trying to launch the boat they capsized it.”

Unseaworthy craft. Leaking hull. Inexperienced crew. All could have been factors in the disaster. We’ll never know for sure. William Herbst said, “You see, that’s one of the lessons you should learn if you’re a yachtsman –stick with your boat. Don’t get out — don’t get away from it.”

On a late August day in 1998, members of the Southwest Michigan Underwater Preserve committee, headed to the wreck site of the Verano. With the son and grandson of captain Ernie Wingard. In addition to scuba gear, they also brought with them underwater communication equipment and bottom to surface video equipment. Their intent– to take the Wingards on a live tour of their father’s vessel which has been on the bottom for over 50 years. For the Wingards, it was a visit to their past. John Wingard said, Father had been the captain of the Verano in some of its better days as a luxury yacht for some very wealthy people up north. And its a very large part of family history for the Wingard clan.

Charles Wingard recalls, “I remember going on board her. She was at Jesiek’s, and she was at the main dock, and bow toward you as you walked out. Just beautiful. And I remember a lot of lower windows in the stern part there and looking in at the furniture and the things in her and also at the time they had a ship-to-shore telephone on there. It was like “wow”.

Brother John Wingard added, “I get to see some of the engines I expect to see and that I’m sure my father crawled over and fussed over. They were a big part of his life, and my son will be with us, and I’m glad to be able to have the opportunity that he can get a little hands-on connection with the early family history.”

The Verano now sits at rest. A small chapter in Great Lakes maritime history has been closed. And a mystery solved. But thanks to the efforts of many concerned and enthusiastic people, that chapter is not forgotten. It’s a chapter that spanned a rapidly changing period of our American history. The remains of the Verano are there for those that want to experience a part of that history.

Story adapted from a video script written by Valerie van Heest and Robert Gadbois.