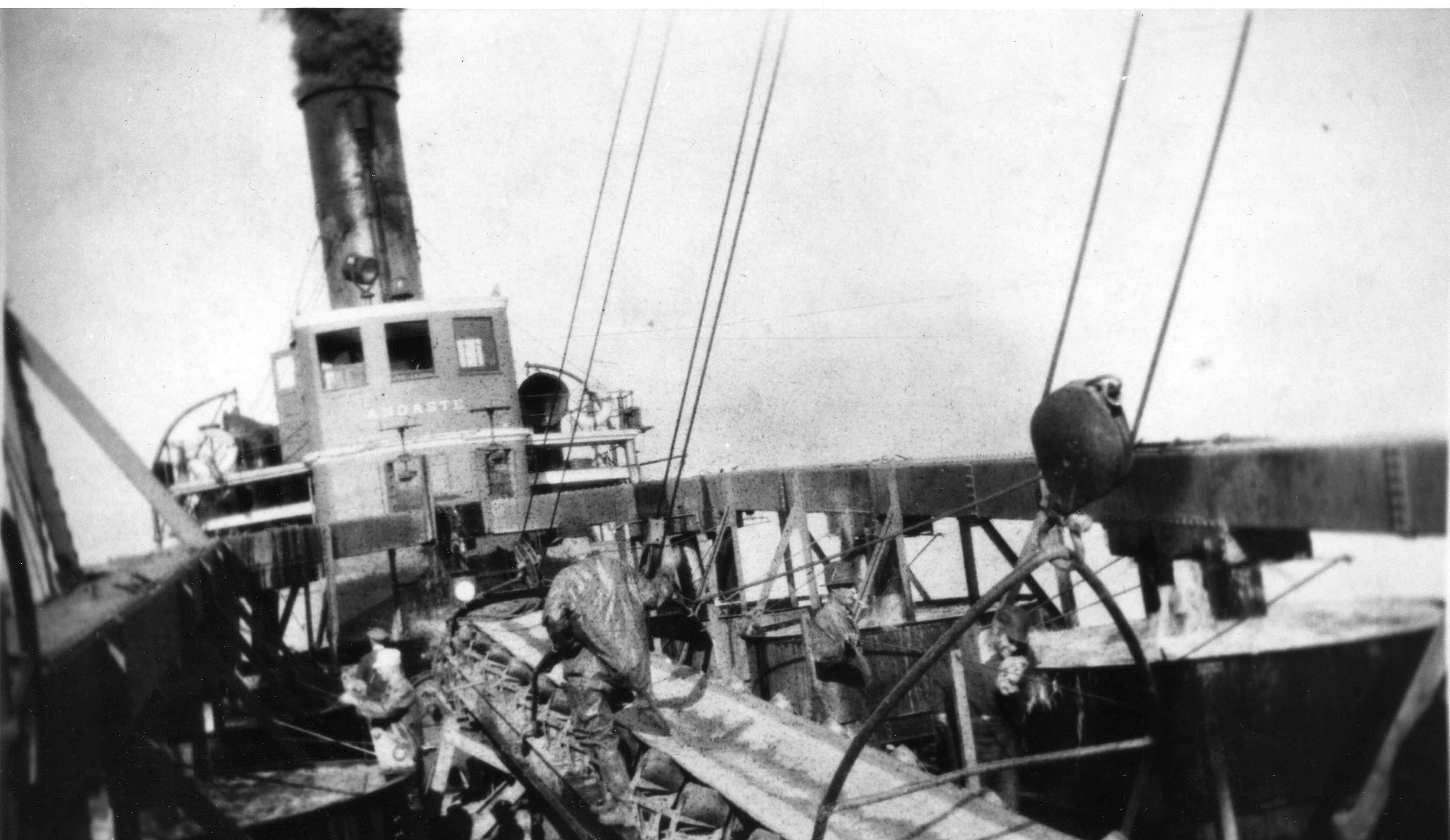

By all accounts the semi-whaleback Andaste was an ugly ship. This strange looking, slope-sided ship was 266 feet long when launched into the Cuyahoga River at the Cleveland Ship Building Company docks in 1892. The steel hulled ship had a beam of 38 feet and a cargo capacity of 3000 tons.

Built for the Lake Superior Iron Company, the Andaste sported the latest triple expansion steam engine with a 36″ stroke, supplying 900 horsepower at 90 revolutions. Scotch boilers, eleven feet in diameter and twelve feet in length, each with two furnaces, made the Andaste a powerful ship.

The Andaste was a sister ship to the Choctaw, also owned by the Lake Superior firm. Both plied the Great Lakes with loads of coal, pig iron, and iron ore until 1898 when the company went bankrupt. The ships were then sold to the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company.

The Choctaw was lost in 1916 when she was rammed and sunk by the Canadian steamer Wacondah in Lake Huron. She lies in 275 feet of water.

In 1925 she was sold to the Cliffs-L. D. Smith Steamship Company. Manager Leatham D. Smith had designed a self-unloading system that would prolong the lives of older ships by allowing them to unload anywhere, without the need for expensive dockside equipment.

The ship was adapted and large derricks and other structures were added to her decks, making the iron boat even more top-heavy.

In 1928, the Andaste was chartered to the Construction Materials Company of Chicago supplying their south Chicago docks with sand, gravel, and other material as needed. Her captain was Albert L. Anderson of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin.

On the afternoon of Monday, September 9, 1929, the Andaste was docked at Ferrysburg, Michigan, up the river from Grand Haven, taking on a load of gravel. She passed the Grand Haven harbor pier heads at 9:03 PM, heading west-southwest across the southern end of Lake Michigan toward Chicago. Not many people paid attention since she made this journey four times a week. She was due in South Chicago Tuesday morning.

At about ten PM, a stiff wind arose, later becoming a full gale. The Andaste was noted to be late on Tuesday morning but no alarm was raised until Wednesday since the old ship often was tardy. With no radio, there was no way to ascertain the fate of the ship. After two days, however, it was feared the ship was lost.

Then, wreckage began to drift ashore along the Lake Michigan beaches from Grand Haven to Castle Park, south of Holland. George Getz, owner of the Getz Farm north of Holland discovered an oar and other pieces of wreckage. At Castle Park, the first body was recovered. Others washed ashore at Grand Haven. The bodies of 16 of the 25 crew members ultimately floated to shore, 11 of them wearing life jackets.

The crew consisted of 25 men.

Captain Albert L. Anderson of Sturgeon Bay, WI

Capt. Charles Brown of Grand Haven, MI, First mate

Joseph McCadde, Cleveland, OH, Second mate

John Anderson, deckhand

James Bayless of Benton Harbor, MI

A. Bluechelt of Grand Haven, MI

Thomas Godas, fireman

Clifford Gould of Lincoln, NE, engineer

Max Green, deckhand

Orville Johnson, of South Dakota

William Joslin of Grand Haven, fireman

Frank Kasperson of Grand Haven, MI, cook and watchman

Chief Engineer Claude J. Kibby of Benton Harbor, MI

William Lorenz, Grand Rapids, MI

Harry F. Lutz, Benton Harbor, MI

Fred Nienhouse of Ferrysburg, MI, crane operator

George Rathcliff, fireman

H. Raymond

Henry Schuitema of Grand Rapids

Darwin Smith of South Dakota

Theodore Torgeson of Owen, WI, wheelsman

George Watt, of Grand Haven, MI, 2nd cook

Harold Whittaker

Ralph Wiley, Benton Harbor, MI, assistant engineer

14 year old Earl Zietlow, a youth on his first voyage

The Van Zantwick Funeral Home in Grand Haven handled the arrangement for the 16 victims whose bodies eventually washed up on the shores of Lake Michigan.

A full inquest was held in Holland resulting in the statement that the ship was in good condition and there was no “laxity” on the part of those in charge.

The jury of prominent Holland businessmen including Mayor E. C. Brooks, Wynand Wychers, Henry Winters, Fred Beeukes, E. B. Stephan, and William Vissers, made three far-reaching recommendations as a result of the trial:

1. That all ships be equipped with wireless (radio)

2. That a central marine office be located where delays are reported

3. That proper search and rescue facilities be maintained on all of the Great Lakes.

Captain George Van Hall, who took accurate current readings on the day following the sinking and whose tug Bertha G. had discovered the first wreckage, testified it was his opinion that the Andaste sank 25 or 30 miles out in the lake. John Swift, a cottage owner between Holland and Grand Haven told jurors at the inquest that he was awakened by a terrible storm at 1:00 AM and saw lights from a ship, apparently close to shore. the lights remained until about 4:00 AM. Newspaper reports of the time speculated she may have sunk in about 60 fathoms (360 feet) off Port Sheldon, north of Holland.

As with all missing ships, the Andaste may never be found. However, with today’s side scan sonar and other electronic search equipment, the secrets of “ships gone missing” may someday be uncovered.

Recent publicity led to MSRA acquiring an original name board from the Andaste in 2012. The item had been stored by a local resident since 1929.

MSRA also met with Karen Reszewski, the niece of Andaste victim Henry Schuitema, who provided detailed information about the aftermath of her uncle’s passing. His body was among the nine that were never found.

Information from newspaper accounts of the time:

Holland City News, Holland Evening Sentinel, and others.