Sometimes the best information about a wreck comes from a well written newspaper article, like this one from Chicago:

SUNK IN MID LAKE

Passenger Steamers Pilgrim and Kalamazoo Collide.

She Lies Under Five Hundred Feet of Water

PASSENGERS AND CREW SAFE

They Were Transferred to the Decks of the Pilgrim.

Wonderful Coolness of the Officers and Men—Statements Regarding the Disaster.

“As the result of a collision in the middle of Lake Michigan shortly after midnight Tuesday night, the passenger steamer Kalamazoo, bound from Holland to Chicago, lies on the bottom of the lake under 500 feet of water, and the steamer Pilgrim, also in the passenger service, bound from Chicago to Saugatuck, lies at O’Connor’s dock at the foot of Illinois Street in a very badly damaged condition.

Luckily, though, both boats had full crews and goodly passenger lists, and a terrible panic succeeded the crash of collision, no lives were lost. That that is true is due no doubt to the admirable coolness and prompt action of the officers and crews of both boats.

In an instant after the collision there was wild commotion on board both steamers, but particularly on the Kalamazoo. There were several passengers on board, three of whom were women. Awakened by the shock, they rushed frantically into the cabin and their screams added to the panic. Captain Cummings had been thrown violently against the door jamb of the pilot house in the crash, putting great gashes in his face with the broken glass. He at once realized that he must get his passengers on board the Pilgrim, which lay alongside, the lake being as quiet as a millpond. The Women were literally carried by the sinking boat’s crew to the Pilgrim. All were in their night-clothes, but one of them had seized her wearing apparel as she had fled from her stateroom and still carried it in her hand. Another went crying from the end of the cabin to the other, shrieking, “Where is my husband?” until she, too, was carried to the Pilgrim, her rescuer assuring her that her husband was already safe on that boat.

Sank in Three Minutes.

As soon as the passengers had been removed the crew returned to the Kalamazoo and secured everything of value that could be quickly carried away. The boat was fast sinking, and in less than three minutes afterward, or some ten minutes after the collision, she sank decks-to. She was now full of water, but was held up by the woodwork and the air in various recesses about her decks.

Lines were attached to the floating hulk and the Pilgrim started to tow it ashore. It was not long before it was discovered that the water was pouring into that steamers hold as well, and all hands set to work with a drill to remove the cargo from the bow to the stern in order to hold the crushed timbers of the bow above the water line. In this they were successful, and the Pilgrim started to pull the wreck of the Kalamazoo back to Chicago, but this harbor was forty miles away and slow progress was made.

All the rest of the night the Pilgrim kept up continuous signals of distress with the hope that some tug or steamer would come to its assistance, when it would have been easy work to have got the Kalamazoo into shoal water. The latter kept sinking inch by inch, and finally went down. For some time after the wreck was entirely under water with the exception of her spars, the four-inch line running to the Pilgrim holding her up, but when it became certain that no aid was to reach them in time, this line was finally cut she sank in 500 feet of water at 8:12 o’clock Wednesday morning. The Pilgrim then continued on her way to this city, reaching here late Wednesday afternoon.

The Pilgrim, as she lay at O’Conner’s dock, at the foot of Illinois street last night plainly showed the terrific force of the collision. The stem was bent and twisted out of all shape, while the solid planks and timbers of the bow were crushed in on both sides, giving evidence that she had pierced the Kalamazoo not les that five feet. Had she been carrying her usual load she must have sunk very soon after the Kalamazoo had, and the crews and passengers of both boats would have been forced to battle with Lake Michigan in lifeboats and on rafts.

Nothing Saved

Three hours after the collision, and while the Pilgrim was towing the half-submerged wreck, Captain Cummings, of the Kalamazoo, Captain Brittain, a passenger on the Pilgrim, and himself a steamboat owner and navigator: Joseph Lewis, mate, and Henry Paxton, second engineer of the Kalamazoo, went back on board the wreck in order to look after the lines and keep them secure. They remained aboard, until heeding the urgent appeals of those on the Pilgrim, and only deserted the hulk barely before she sank from sight. Only a portion of the Kalamazoo’s books and papers were saved. Some of the ship’s cash was even lost overboard, and the passengers and crew even lost their effects, even part of the wearing apparel they took off when they retired. The passengers speak in terms of praise, however, of the officers of the Kalamazoo and also of the Pilgrim, and say that had it not been for the cool conduct of those officers loss of life must have ensued through the panic among the passengers.

Captain Cummings took his entire crew to the office of Charles E. Kremer, the admiralty lawyer, and the affidavits of every one of them were taken in anticipation of the suit.

Captain Cummings’ Statement.

“It had been foggy all the early part of the night,” said Captain Cummings, “but at midnight it had begun to clear up, and the fog lay in banks on the lake. We heard the Pilgrim fully a mile away and she heard us at about the same time, for she sounded signals that she would pass to starboard. We answered this signal and supposed that we would pass each other all right, as we had done a thousand times before. Had neither boat tuned its wheel we ought to have passed about 300 feet apart, but I ordered the wheelsman to put the wheel to port, in order that the distance might be still farther. We were swinging away from the Pilgrim when she suddenly turned toward us, and the next thing was the crash. I had my hand on the wheel when the Pilgrim struck us, and was thrown against the door jamb with great force. Of course, I did what I could to save the passengers first of all. AI now believe that if I had not had an extra supply of coal on board my steamer would have floated until we could have got her into shallow water. We would have held on to the line which kept her up, but it did not seem as if there was any use of longer continuing the struggle, as we were forty miles from port. I have been sailing since 1857, and have been master of sailing and steam vessels for twenty-two years, and this is my first accident.”

Captain F. A. Sears, of the Pilgrim, filed the following brief statement under oath:

The Pilgrim left Chicago for Saugatuck on the evening of May 24. we had eleven passengers and our crew numbered twelve. It was thick and foggy all night. Wind four miles an hour; no sea. It was dark. At 12:40 a.m., May 25, the Pilgrim collided with the propeller Kalamazoo. We had been blowing our whistle continuously before that. We heard one whistle from the Kalamazoo and saw her headlight and green light. The two steamers came together immediately after. The Pilgrim struck the Kalamazoo twenty-five feet aft of the port bow. We took off the crew and passengers of the Kalamazoo. We could make no headway and the Kalamazoo went down forty-five miles northeast of Chicago piers we were steering the proper course-the one we usually take from Chicago to Saugatuck. The Pilgrims stem and bow are damaged to the extent of $2,000. It was the mate’s watch at the time. I had been lying down only forty minutes when the collision occurred.

The captain said afterward that the fog was low down on the lake, and that a short time before he had noticed the stars shining brightly. Captain Brittain, who was asleep when the collision occurred, corroborated Captain Sears, and said he saw stars half an hour before the accident occurred.

The Basis of the Suit.

The basis of the suit which will be at once instituted against the Pilgrim will be that in passing, her wheel was put the wrong way. It is said that the mate gave the wrong order to the wheelsman on the Pilgrim, and that he told him to put the wheel to starboard when it should have gone to port. To this charge the officers of the Pilgrim make no reply, but rely simply upon the statement that they were on their proper course, while the Kalamazoo was four miles from where she ought to have been. Both boats were going at full speed, so the crews of each admit, and the engines of the Pilgrim continued to work some time after the collision, showing the crash was a profound surprise to those in charge.

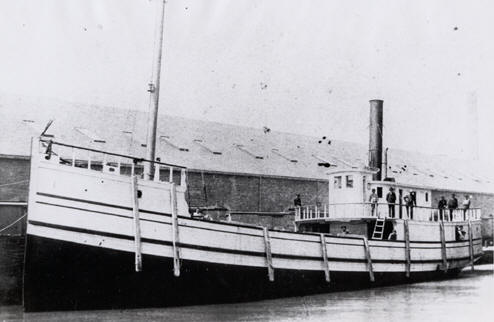

The Kalamazoo measures 286 tons, was built four years ago, rated A-1, and was valued at $26,000. There is no insurance.”