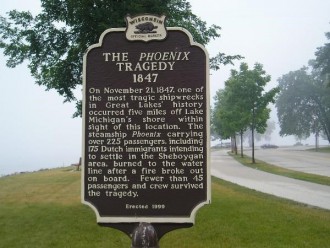

The Phoenix – Lost off Sheboygan, Wisconsin, November 21, 1847

Hundreds of thousands of separatists throughout Europe, caught up in the famine and political and religious intrigue of the mid 19th century, began to emigrate. Many of these were from Holland…the Netherands. And for many of them, the rich farmlands of America’s Northwest territory beckoned. Thus began the journey for many of those who would eventually lose everything just five miles short of their destination.

So began the first leg of their journey — on foot or by wagon westward to the port of Rotterdam.

In the mid-1800s, the journey to America was long and difficult. Immigrants arranged and then waited for a steam or sailing ship to take them to America.

Poor immigrants traveled to America on ships that were making their return voyage after having brought tobacco or cotton to Europe, often waiting at the dock for weeks until the below decks space was filled to capacity with human cargo. Yes, these vessels were built for cargo — not for passengers. Accommodations were crude at best. This group of Hollanders left Rotterdam aboard the ship called the France.

The voyage took between 30 and 60 days, depending on the wind and weather. In steerage, ships were crowded with each passenger having about two to four square feet of space. Lice and rats were prevalent. And passengers had little food and no ventilation. Between 10 and 20% of those who left Europe typically died on board these ships.

The France arrived at New York in late October 1847. And then, from New York the immigrants traveled more than 300 miles more, via the Erie Canal to the town of Buffalo, New York, where they waited again to board another vessel for the last leg of their journey to Wisconsin.

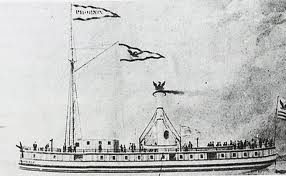

After some time, they booked passage on a new ship, a steam driven propeller named Phoenix.

These “propellers” were slowly replacing the venerable side wheel steamers that had ruled the Great Lakes for the first half of the 19th century.

Built just two years earlier at Buffalo, the Phoenix was 141 feet long, and 22 feet wide. She was a steamer with a still very new, twin-screw propulsion system.

On November 11, 1847, the Phoenix lay at her dock in Buffalo, New York, taking on the last of her cargo of coffee, molasses, hardware and chains, as well as hundreds of passengers. This was her last scheduled voyage of the shipping season. Sadly, the Phoenix was never designed to carry so many passengers.

Only 25 of the American passengers enjoyed cabin space. The Dutch immigrants were crammed anywhere they could find room. Of the close to 300 souls on board, only 50 to 70 were Americans, and the rest, maybe as many as 200 to 250, were immigrants, mostly from Holland. Their clothing was strange, and their language even stranger. But they were a sturdy people, hardened by years of working their farms.

The Phoenix was regularly engaged in the very lucrative trade of transporting immigrants from Europe who were flocking into Buffalo for transport to the farmlands of Middle America.

The voyage through the Great Lakes was routine enough for the Phoenix crew: They would steam west the length of Lake Erie from Buffalo to Cleveland and on to Detroit. After a layover in Detroit, they would steam north through Lake St. Clair, entering Lake Huron for the north run to the Straits of Mackinac. And then south on Lake Michigan to their destination of Sheboygan.

Although a land route was available for foot and wagon travel, most immigrants considered the water route through the Great Lakes to be both safer and easier than to travel overland to their new homes in the Midwest. After all, they had just crossed an ocean.

From the beginning, this journey was plagued by misfortune. Under the capable hand of Captain Benjamin G. Sweet, the Phoenix encountered tremendous seas on her westward journey on Lake Erie.

Just off their first port of call at Fairport, Ohio, during the night of Saturday, November 13, 1847, heavy seas knocked Captain Sweet off his feet, severely bruising his left knee. Inflammation set in and the pain was so severe that the captain took to his bunk. He would be bedridden for the remainder of this trip.

First officer Watts, a veteran great Lakes sailor from Cleveland, took on the role of “acting captain” for the remainder of the voyage.

The Phoenix called at Cleveland and Detroit and then made her way up the St. Clair River into Lake Huron.

A howling north wind drove straight down the big lake. Great mountains of water smashed at the Phoenix trying to drag her under. The storm was unrelenting. After several days, the weather calmed for a time and the Phoenix turned her bow westward toward the straits of Mackinac.

But things changed again as the Phoenix made the turn southwest from the Straits. Strong, gale force winds roared across the lake, drenching the decks once again.

On Wednesday, First Mate Watts, after conferring with Captain Sweet determined to seek shelter and wait out the weather in the lee of Beaver island. Two days later, the vessel was underway. But the weather again turned foul.

As the vessel struggled south down the eastern shore of Wisconsin, excitement aboard the ship grew. The immigrants realized that once they reached Manitowoc, they had only a short journey to Sheboygan.

The Phoenix carried cargo for Manitowoc and needed to replenish its fuel supply there. Saturday night, the crew spotted the lights of Manitowoc and, about 45 minutes later, they made the harbor entrance. The captain gave orders to lay over for a few hours until the wind abated. Some of the crew — those not involved in the unloading of cargo and the taking on of firewood for the boilers — were given permission to go ashore. Later it was whispered, but never verified, that key crew members returned to the ship drunk.

At 1:00 am, when the weather eased, Watts blew the ship’s whistle, which rallied the crew aboard, and got underway, this time, heading to Sheboygan – just 25 miles to the south — the last leg of a months-long journey for the more than 200 Hollanders aboard the Phoenix.

Working up a full head of steam, the firemen kept the boilers stoked and the fires hot. They were making great time as the lake was flat calm with no wind in the cold, crisp November air.

With the lights of Sheboygan glimmering just five miles to the west, nearly all of the passengers were asleep. Those who weren’t, were anxious for their journey of nearly 4,000 miles to be over.

But something was wrong! The engine sounded different. Some of the passengers urged the crew to investigate, but were told to mind their own business. Smoke was seen in the engine room, and chief Engineer House raised the cry. The boiler had become red hot due to a lack of water, setting fire to the ceiling, woodwork and cords of firewood stacked all around it.

At first, the flames seemed manageable and caused no great alarm, but suddenly, the flames mushroomed and began to billow from the engine room windows. It was rapidly becoming very apparent that the ship was in serious trouble.

Captain Sweet, still confined to his cabin, was wakened, and he immediately ordered that all fire hoses be laid and steam pumps be put into action against the raging flames. The helmsman was ordered to make for the shore with all possible speed.

The passengers were organized into bucket brigades, but it was no use. The Phoenix was doomed.

As the passengers awoke to their fate, the scene turned to utter confusion. Mothers grabbed their babies. Fathers began to look for ways to leave the doomed vessel. Many of them still in their nightclothes. Making things worse — the Phoenix had only two small lifeboats, with room for perhaps 20 people each. There were nearly 300 on board. These two boats were lowered.

Although arguing to remain with his doomed boat, the injured Captain Sweet was lowered into a lifeboat by his crew, where he took command. Watts commanded the other boat.

A 20 year old Hollander named Derk Voskuil found his way to the rail where those loading the boats told him to get aboard and help row toward shore.

19 year old Hendrika Landweerdt and some of her family also avoided the flames long enough to approach one of the boats, which Hendrika was allowed to board. As the already overloaded boat pushed away, her two year old sister Hanna was tossed down to her by her parents.

This boat already held 21 of the cabin passengers and a few immigrants. The other boat held 22 more. These 45 people, and three others were the only survivors of the Phoenix disaster.

Derk Voskuil and Hendrika Landeweerd were among them.

Hendrika’s parents and four of their other children died in the fire. Hendrika’s two older sisters survived.

In his memoir, survivor Dirk Voskuil stated that after his boat lost an oar, he helped by rowing with a broom. And later, as the boat began to leak, he used his wooden shoes to bail water from the small craft.

Back on the Phoenix, the flames spread from the midsection of the boat toward both the bow and the stern. The passengers could only hope that someone on shore or perhaps another vessel might see their plight and send assistance. But with each passing moment, hope turned to despair.

Facing death by drowning or freezing to death in the frigid waters of Lake Michigan, or being burned alive by the flames consuming their ship, despair quickly turned to panic as passengers and crew trampled over each other seeking a few more minutes of life.

Some opted to hasten the end by jumping into the frigid lake. Others climbed high into the mast, only to find the flames climbing right behind them, forcing them to drop back onto the deck.

Others began tearing apart anything that might float, and tossing these improvised lifeboats overboard. Those who clung to these bits of flotsam and jetsam soon froze to death in the icy waters.

Several of the younger immigrants, who had met and fallen in love during their months of travel and who were planning to marry, decided to spend eternity together, calmly joined hands and jumped into the water. Entire families embraced and lept into the icy waters of Lake Michigan.

On shore in Sheboygan, the flames were noticed. Aboard the steamer Delaware, it took nearly 90 minutes to get up enough steam to leave the dock and head toward the stricken vessel.

By the time they arrived, the upperworks of the Phoenix had burned almost to the waterline.

They found three men alive: Chief Engineer House, floating in the water — and ship’s clerk Donihue and a passenger named Lang both clinging to the rudder chains under the stern.

By morning’s light, the gentle November breeze was just as cold as ever. Not a ripple broke the glass-like surface of the lake, but the once-proud ship was now a drifting, burnt-out hulk. Soon, bodies were coming ashore at Sheboygan.

The Phoenix had been launched only 18 months earlier, and now she was a burnt-out, smoking ruin. Only a small portion of her forward cabins remained. Her tall stack was gone, having crashed over the side at the height of the fire.

Captain Tuttle and the crew of the would-be rescue boat, Delaware, took the burned out hulk in tow and headed into port. It was now nearly 6:00 am. Dawn broke across the lake. It was Sunday morning. The towing operation proceeded smoothly until the vessels approached Sheboygan.

Suddenly the forward structure of Phoenix collapsed, tossing, among other things, the ship’s safe into the lake. It has never been recovered.

Hundreds of people lined the shore and the wooden pier as the Delaware approached.

The last journey of Phoenix was over. She had reached her final resting place. The local coroner, James Berry, boarded the wreck and removed several charred bodies. These were placed in a makeshift morgue in an empty storefront.

The next morning, wagons were sent north up the lake shore, looking for survivors.Approximately seven miles north of Sheboygan, they located the two lifeboats and a pitiful group of survivors who were quickly taken back to the city. Of the 45 or so survivors, 25 of them were dutch immigrants. They arrived in Sheboygan destitute.

Over the next days, the residents of Sheboygan opened their homes and their hearts to the refugees. Clothing and money were collected and given to the sufferers. Some of the immigrants had relatives in the area who had preceded them to the new world. Others were left alone in a strange land.

One by one, the few survivors fanned out across the countryside, some settling in the Sheboygan area in the vicinity of Cedar Grove, Holland, and Oostburg. A few crossed the lake and settled in Michigan. Many lived to an old age, but all of them told and retold the story of the night their lives were forever changed.

While the exact death toll of the Phoenix disaster will never be known, it still ranks as one of the greatest losses of life in a single incident on the Great Lakes.

The burned out hull of the Phoenix settled in eight feet of water near the end of the dock in Lake Michigan. That winter, severe storms ripped off the bow section and carried it ashore where the timber was salvaged by a local farmer. In the spring of 1848, the boilers and other any machinery that could be re-used was salvaged. The wreck was then abandoned. Time passed. The dock at which the Phoenix was abandoned fell into disuse, and one by one, the survivors of the Phoenix disaster passed away. The last died in 1918.

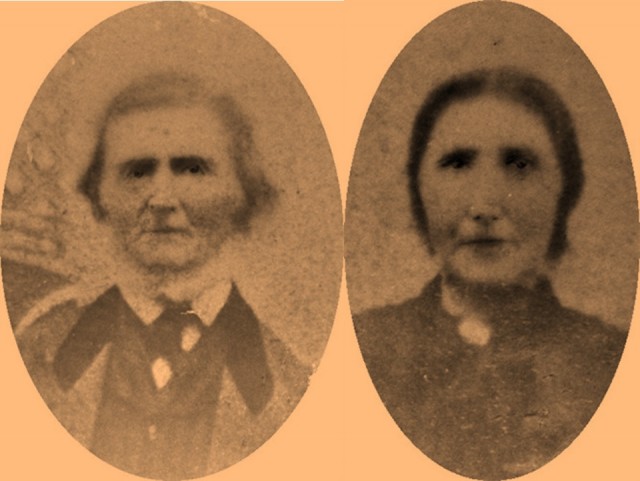

But what of Derk and Hendrika? The two, joined by disaster, were married and bought 30 acres in nearby Cedar Grove, WI, where they built a 16 by 20 foot cabin, like this early Wisconsin pioneer home. They lived the rest of their lives together — forever bound by their experience on the Phoenix.

Hendrika died in Cedar Grove in January, 1884 at the age of 57. Derk died there in February 1901. He was 83.

Hendrika died in Cedar Grove in January, 1884 at the age of 57. Derk died there in February 1901. He was 83.

They are buried side-by-side in Cedar Grove Cemetery.

Text for this page is comprised of excerpts from a multi-media program developed by MSRA director Craig Rich.