Thursday, September 25, 1980 dawned as a beautiful early autumn day on the shores of Lake Michigan. Three young men from Holland, Michigan and a fourth from Cleveland, Ohio had spent the day attending a popular annual boat show at McCormick Place in Chicago. The three Holland men worked at Bay Haven Marina in Holland and one of them, former U.S. Coast Guardsman Curt Anderson had volunteered to bring a boat back to Holland for the owner who had recently traded it in at Bay Haven Marina.

Anderson and co-worker Steven Brower, the two married men in the group, phoned home to inquire about the weather conditions across the lake. The men were advised that the weather was calm.

The 32-foot Trojan yacht SeaMar III left Montrose Harbor, north of Chicago at about 4:00 PM and headed northeast toward the eastern shore of the big lake — about 90 miles away. The evening crossing would take them 4 to 5 hours, depending on weather conditions.

Before casting off, the experienced sailors made a thorough inspection of the boat, as witnessed by the vessel’s owner, who was there to see them off. As they were familiarizing themselves with the vessel, ominous clouds appeared in the sky, but no storm warnings were posted prior to departure.

Curt Anderson, Steve Brower, Mike Stephenson and Harvey Willsey were never seen again. The vessel did not arrive as planned at the anticipated time of 10:00 or 11:00 PM that evening.

The vessel was a 1974 32-foot, Trojan-F32, a true pleasure craft with a flying bridge, large plate glass sliding doors and a roomy salon and cabin.

A storm had kicked up during the evening and gained unusual intensity. The wives of the two married men became concerned and tried to raise the vessel on a marine radio, but to no avail.

Knowing all four men were experienced sailors and had made similar crossings in the past, no one had yet become unduly alarmed. In fact, with Anderson, a former U. S. Coast Guard member who had participated in many search and rescue missions, the others could not ask for a more experienced pilot. He was familiar with handling small boats even in severe weather conditions. In fact, all four of the men were boaters and three were employed in the industry.

Being experienced Lake Michigan sailors, the men knew how quickly the lake could change. No doubt if the weather became too rough, they would alter course to due east, and make for a closer port or “hug” the eastern shoreline of Lake Michigan for what small protection it might lend.

Back home, the two wives slept uneasily that night and upon rising Friday morning, September 26, they alerted the U. S. Coast Guard in Holland to report the men overdue and the boat missing. The Coast Guard receives many such calls, only to learn that the missing boat put in at another port to ride out the storm. However, at daybreak the Coast Guard began contacting various ports along the eastern shore of the lake to learn if the Sea Mar III had been sighted. There was no word. No sightings. Anxiety grew.

Soon, one of the largest and most extensive air and sea, search and rescue missions in the history of Lake Michigan was launched. The U. S. Coast Guard ninth district in Cleveland, Ohio directed the effort. Numerous surface vessels, fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters would join in a concentrated search of the southern third of Lake Michigan. The search corridor was determined by drawing a line on a chart directly between the two ports, then searching the vast area along lines five miles on either side of the direct route.

Friday passed without any sighting of the boat or debris. The search area widened and by Saturday, more vessels and planes were pressed into service. By then, news of the missing craft had reached the local media. The general public joined in the anxiety for the missing crew.

Complicating the efforts was the fact the searchers did not know what they were looking for; a disabled vessel floating on the surface? An overturned craft barely afloat? Crew members in life jackets clinging to wreckage?

On Sunday, the Coast Guard announced that if something did not turn up soon, they would have to call off the search. Within a few hours, reports began to come in about debris being found. By afternoon, a trail of debris was located and numerous items were recovered including two large engine hatch covers, a smaller hatch cover, foam cushion material, a flare gun kit (intact and unused) and several empty orange life jackets.

Each item, prior to being brought ashore, was tagged with information on where and when it was discovered including the latitude and longitude. Finally, several days later, a white life ring washed ashore bearing the name, “Sea Mar III”.

All of the items were brought to the U. S. Coast Guard station at Holland and identified by the boat owner, who had driven around the lake after hearing about the lost vessel. There was no doubt now that the small boat had sunk during the storm. Would the bodies of the four men ever be recovered?

Rumors began to circulate about the mysterious sinking. Some even questioned whether the whole event was, for some reason, staged. These were quickly dismissed. After all, two of the men were happily married. All four were men of good character, who had good jobs and many friends. If not the crew, then what was there about the boat that may have led to this disaster?

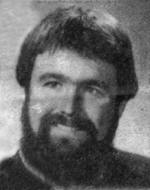

Enter John L. Coté, a Lansing attorney who lived in Holland and kept a boat at the same marina. Coté had known three of the four young men for some time. He knew them well enough to know that something must have been wrong with the boat for this to happen.

After learning that an identical vessel was for sale, and docked at Bay Haven Marina, Coté obtained the keys and began to look for clues. A thorough examination revealed nothing out of the ordinary. The vessel appeared well built and sturdy. Inspecting the bilges Coté was impressed by the size of the two engines and the large fuel tanks. They left little room to maneuver around down below. He was just about to conclude his inspection when something caught his eye. A shaft of light was streaming into the bilges from the rear of the vessel. Where was that much light coming from?

Trojan F32

Coté went topsides again to take a closer look at a large metal cowling with vents facing forward that was located on each side at the stern of the boat, only about two feet above the waterline. It was an air vent, designed to bring fresh air into the bilges to help exhaust engine and gasoline fumes.

The vent cover was 18 inches long and 8 inches high. It seemed rather large –almost like a heating or cooling register. And the vanes were facing forward. Coté though this curious.

A similar sized opening was located on each side of the vessel, amidships. Its vents faced aft — exactly opposite of what a normal airflow would seem to suggest.

Coté, who had no knowledge of marine design, thought there must be a reason. It would be months before he learned about a manufacturer’s recall campaign that had occurred in 1978.

To compound the problem, the vessel’s only bilge pump was located near the bow or front of the boat, unable to pump the water from the rear of the vessel as it was underway. The normal flow of bilge water in a vessel underway would be toward the stern where the SeaMar III had no bilge pumps.

Was it possible that enough water accumulated in the bilge of the boat to disable its engines and send the craft to the bottom?

Coté decided to represent the families of the missing men in what turned out to be a ten-year ordeal, which led all the way to the federal appeals court.

Parallel courses were set upon. A private search for the vessel would begin. Research into admiralty law and product liability law would begin.

Coté decided to go straight to the top, and called Jacques Cousteau in Monaco. Cousteau was gracious enough to put Coté in touch with his Cousteau Society in New York. They offered much advice.

The search area was narrowed to a five mile wide by ten mile long corridor between South Haven and Saugatuck. Coté’s son Michael, also a former Coastguardsman, was instrumental in deciphering the Coast Guard’s reports of debris location. Each item was meticulously detailed on a chart of the lake.

Coté then discovered a witness who had heard a radio message from the missing vessel. If true, this was the only known message from the doomed crew. Since the witness’s radio had only an eight to twelve mile range, the searchers overlaid the possible coverage with the location of the debris discoveries and the two sets of data matched.

While the location was closer to shore than a direct route from Chicago to Holland, it was consistent with the route that would haven been taken by a crew attempting to take advantage of the shelter of the shoreline.

Several other witnesses claim to have seen a white light on the lake at about the same time as the radio message was heard. The location of this light also coincided with the debris and radio message.

Over time, the search for clues ended and the incident was settled in the courts in favor of the families.

In 2005, while searching for the remains of Northwest Airlines Flight 2501, MSRA searchers located a 32 foot pleasure craft off South Haven. Anxious that this may be the sunken remains of the SeaMar III and that the remains of the four young men might still be inside, they sent a team of divers to investigate. Jack Coté was standing by in a nearby support vessel. The boat turned out to be a scuttled pleasure craft with no connection to the missing Trojan.

In a final and ironic twist of fate — or perhaps God’s providence — in January 2006, MSRA director Craig Rich discovered a 2nd Sea Mar III life ring! This discovery, however, was not made on the open waters of Lake Michigan, but rather at a West Michigan antique store. Rich spotted the life ring at Depot Antiques in Spring lake and its authenticity has been verified by Jack Coté. The hand written boat name is identical as is the stamped date on the USCG approval tag.

After investigating the life ring’s history, Rich discovered that it was found on a Lake Michigan beach, just south of M-45 about a week after the sinking of the SeaMar III. This fact could shed some new light on the location of the lost vessel and its four occupants.

The life ring was found on the beach by Clinton Bekins of Grand Haven and simply stored away for 25 years before his brother Clifford Bekins sold it to a man who placed it on consignment at the antique store.

The two life rings were brought back together for the first time in 25 years and 4 months on January 22, 2006. it was an emotional moment as Jack Coté held the two life rings from the lost vessel that captured his heart decades ago. Sadly, Jack Coté passed away in December 2015 without the Sea Mar III having been located.

MSRA is dedicated to locating the remains of the SeaMar III and will continue to include potential locations in its annual shipwreck searches. The search effort is further promoted by the donation of a side scan sonar unit by R.J. Peterson of Saugatuck, who also was involved in the search efforts in 1980.

Photo: Jack Coté displays the two life rings found 25 years apart. The one on the left was discovered in the lake shortly after the loss, while the one on the right was located more than 25 years later at a Spring Lake antique store.