The City of Green Bay was so named because it was built in Green Bay, Wisconsin, in 1872 for a businessman named Lambert. After three years he sold it to 30-year old Captain C. W. Elphicke of C. W. Elphicke & Company, vessel owners, agents, and insurance brokers. Elphicke sent it out of the Great Lakes to be used in the Atlantic trade running cargos between South America, Europe, and the West Indies until July 1880, after the ship had been repaired in the wake of a hurricane, Elphicke brought it back to use in Lake Michigan hauling coal and iron ore. In the summer of 1887, Elphicke sold the 15-year-old City of Green Bay to Captain Reed, of Chicago for $9,700.

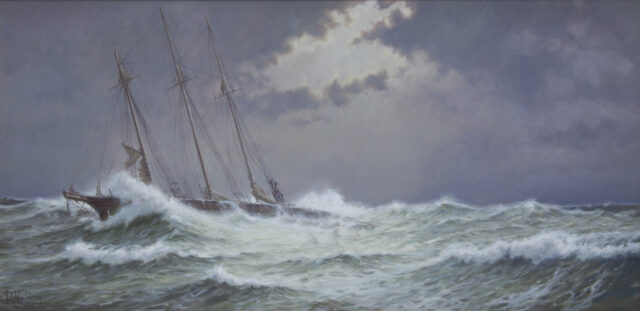

In late September 1887, the City of Green Bay, in the company of another schooner belonging to Captain Reed, the Havana, set out from Escanaba, Michigan, to Chicago with a combined load of about 1200 tons of iron ore, and into the teeth of a northwest gale, which was so strong by early evening that it blew the ships off course, eastward toward the Michigan shore. When Captain P.W. Costello of the City of Green Bay realized he could not steer the ship against the storm, he ordered his five crewmembers to fashion a raft in case the ship sank and to allow the winds to carry them toward the eastern shore of the Lake where they might get close enough to land to be rescued.

When Captain P.W. Costello of the City of Green Bay realized he could not steer the ship against the storm, he ordered his five crewmembers to fashion a raft in case the ship sank and to allow the winds to carry them toward the eastern shore of the Lake where they might get close enough to land to be rescued.

About three miles south of the channel at South Haven, the City of Green Bay careened bow first into the outer sand bar and came to a halt. Waves continued to bash it from the stern. To get out of the raging surf, the crew climbed into the masts and began signaling for help to let the rescuers on shore know they were alive. The life-saving crew set up its Lyle Gun, a small cannon that would fire a shot line out to the wreck that would then be rigged to allow sailors to ride a life ring back to shore much like how a zip line works today.

But the life-savers had trouble with the operation. The storm was too strong for the shot line, causing it to break and the life-saving crew had not brought back up lines. Valuable time was wasted having to send a man back for more line. By the time he returned, they managed to get the line out to the ship, but by then the storm was starting to tear the structure apart. Two of the masts fell, breaking the ship apart and sending three crew members to their death in the raging waters below. To attempt to save the remaining crew, the lifesavers would need to use the station’s surfboat, but they had left that behind and once again had to send members back to cart it down the beach.

More than an hour later when they returned they struggled to launch the small boat against the rollers pounding the beach and it quickly overturned. Once they righted it, there was not a clear path to reach the remains of the ship as so much debris was being tossed about. They eventually hauled two men into their boat, one, the captain had already died, and the other was near death. The bodies of the other four were never found. A. T. Slater of St. Joseph was the sole survivor.

The storm sank or disabled several other ships on Lake Michigan, including the Havana, which in circumstances similar to the City of Green Bay, sank, but in deeper water though. The masts remained above the surface and allowed the crew to climb into them and await rescue. But the St. Joseph Life Saving Crew did not attempt a rescue in their surfboat. Instead, the local tug Hannah Sullivan set out to rescue the crew. By the time they reached the ship, three men had fallen into the water and drowned, but the tug brought the four remaining crewmen safely to shore.

Captain Cross of South Haven resigned in December that year after an investigation was launched into his unpreparedness, which may have resulted in the loss of five lives.

THE WRECK OF THE CITY OF GREEN BAY

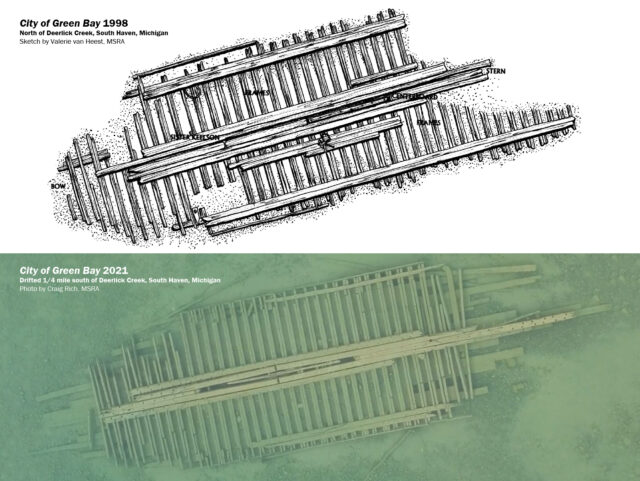

Over the decades since the 1887 loss of the City of Green Bay, the building of homes and cottages along the lakefront minimized public access to the beaches for recreational use. The public gravitated toward the outlet of the winding, multi-branched Deerlick Creek at the foot of 13th street. Some time, perhaps in the 1920s or 1930s when the beach became popular, someone spotted the remains of a shipwreck some 200 feet northwest of the creek mouth just barely covered by the water. Through word of mouth or a visit to the local library, it became clear the wreck was the City of Green Bay. From that point on, the shipwreck became a feature of the little beach.

When a developer bought a sizeable piece of lakefront land north of and adjacent to Deerlick Creek, the title search revealed that the property actually included the river outlet. Citizens, concerned that they would lose access to the beach, approached the township to see if an arrangement could be worked out to maintain public access. The township interceded and through a township fund, contributions raised from a Friends of Deerlick Creek Park group that had formed was able to acquire enough money to purchase the lakefront and 2 acres to develop as an official township park. Word of mouth promoted the shipwreck, which remained easily assemble from the beach as long as visitors respected the private beaches of the homes that were soon built north of the park.

In 2012 a local woman fearing that such regular visitation from tourists and the continued effects of storms and ice would continue to degrade the shipwreck, held a public meeting to solicit support for raising the wreck for display in a museum. Of course, anyone familiar with the raising of the extremely intact schooner Alvin Clark from deep water in 1969 knows the difficulties of such an endeavor. Saturated wood requires years of stabilization in chemicals otherwise exposure to the air will quickly rot the wood. That is an enormously costly endeavor, as is building a shelter to house such a shipwreck after stabilization is complete. Neither the government nor the public would financially support the preservation of the Alvin Clark, and 25 years after it was raised and brought to dry land it had rotted so badly that it had to be destroyed. After that unfortunate circumstance, none of the Great Lake state governments, which are responsible for shipwrecks, have allowed the recovery of an entire shipwreck from state waters, believing that shipwrecks are better preserved in the cold freshwater.

A 2011 satellite image clearly shows the outline of the wreck off the fourth home north of the creek mouth.

An UNEXPECTED DEVELOPMENT

In late May 2021, the owners of a home some distance south of Deerlick Creek contacted the Michigan Maritime Museum in South Haven to report that they had just spotted a never-before-seen shipwreck below their eroding bluff and beach. The Museum contacted its partner, the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, to examine the wreck. Board members Valerie and Jack van Heest and Craig Rich who had some twenty years earlier photographed and taken measurements and produced a drawing of the remains of the City of Green Bay immediately recognized that the wreckage at the base of the bluff as the City of Green Bay. A survey of the place where it used to be confirmed their conclusion: The City of Green Bay was no longer there. While it is unusual for so large a section of ship embedded in the bottom for so long to move, it is not unprecedented.

Record high water levels in 2020 contributed to erosion up and down the eastern shore of the Lake. That, in all likelihood, combined with a massive storm churned up by Mother Nature, lifted the City of Green Bay and deposited it elsewhere.

Record high water levels in 2020 contributed to erosion up and down the eastern shore of the Lake. That, in all likelihood, combined with a massive storm churned up by Mother Nature, lifted the City of Green Bay and deposited it elsewhere.

It is unfortunate that the City of Green Bay is no longer so easily accessible to the public. Fallen trees and eroding shoreline at the base of a series of private homes south of the creek make it difficult and potentially dangerous to try to access the wreck by walking along the surf line. Visiting the wreck may require a small boat. But there is no guarantee that the City of Green Bay will remain. Erosion could certainly bury the wreck, or another storm may further break it up or move it yet again. A shipwreck is a non-renewable resource that will eventually be reduced to nothing even in the preserving fresh waters of the Great Lakes. Therefore it is important to appreciate these historical treasures while they exist and assure that their stories are written so as not to be forgotten in the future. They are reminders of a previous era when the lake was used more regularly for shipping cargo and when sailors risked their lives to keep the economy growing.

By Valerie van Heest

By Valerie van Heest